Memories from Staff and Performers

BILL KLING, PRESIDENT EMERITUS OF MINNESOTA PUBLIC RADIO AND AMERICAN PUBLIC MEDIA

The beginnings of a “live” Keillor show occurred at 6:30 a.m. one weekday in the early 1970s, broadcast on classical music station KSJN. I remember waking up to somebody singing “Old Shep,” followed by the ear-piercing sound of a “glass harmonica” (someone rubbing wine glasses). Bad morning.

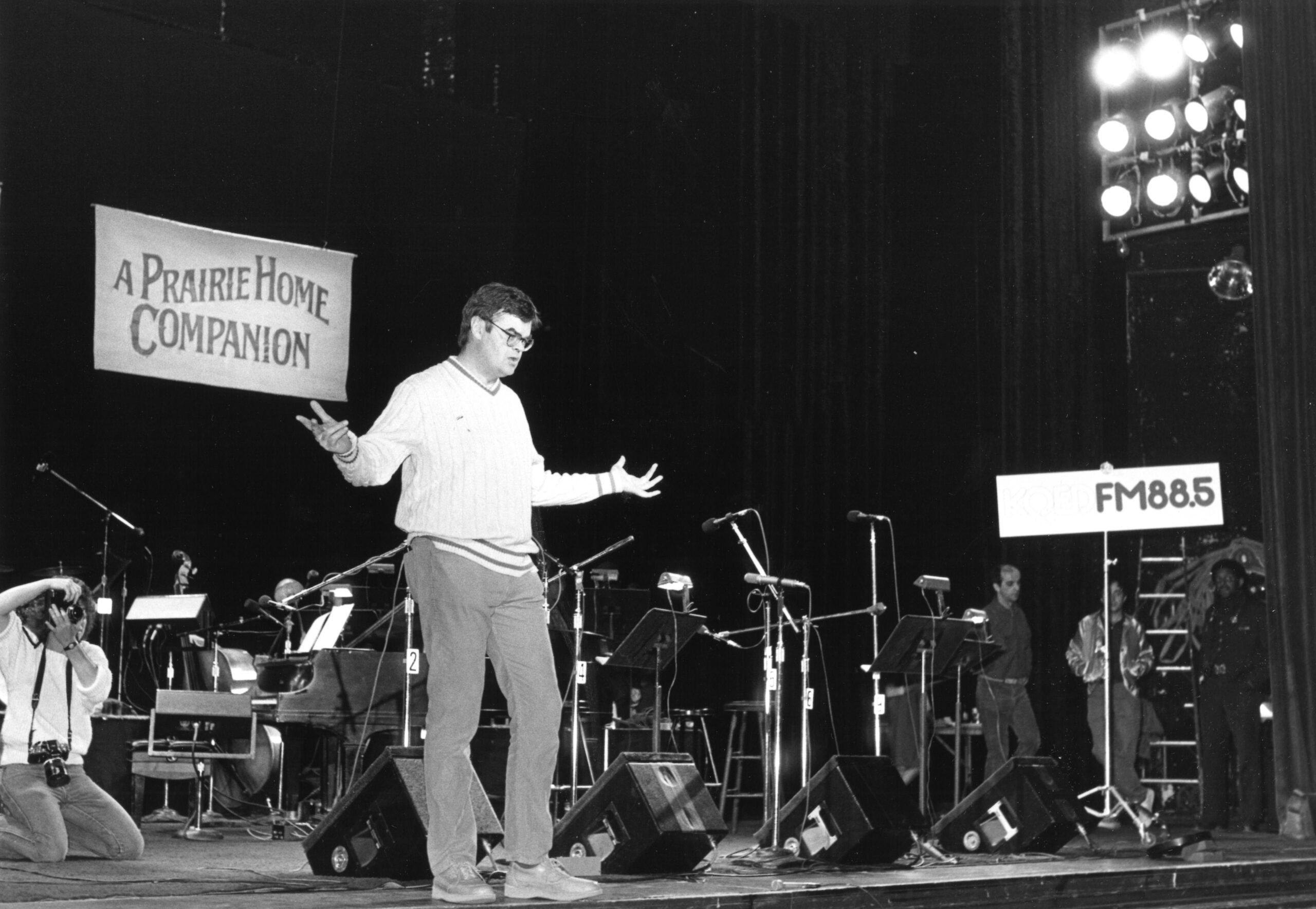

Garrison and I had talked about a time slot when the show might work (6:30 a.m. wasn’t the answer). We settled on Saturdays at 5 p.m., allowing a live audience, already out and about, to come and see it. It was also a time of the week when public radio had a very small listenership so there wouldn’t be an uproar if classical music was interrupted. And we further limited the damage by broadcasting only once a week.

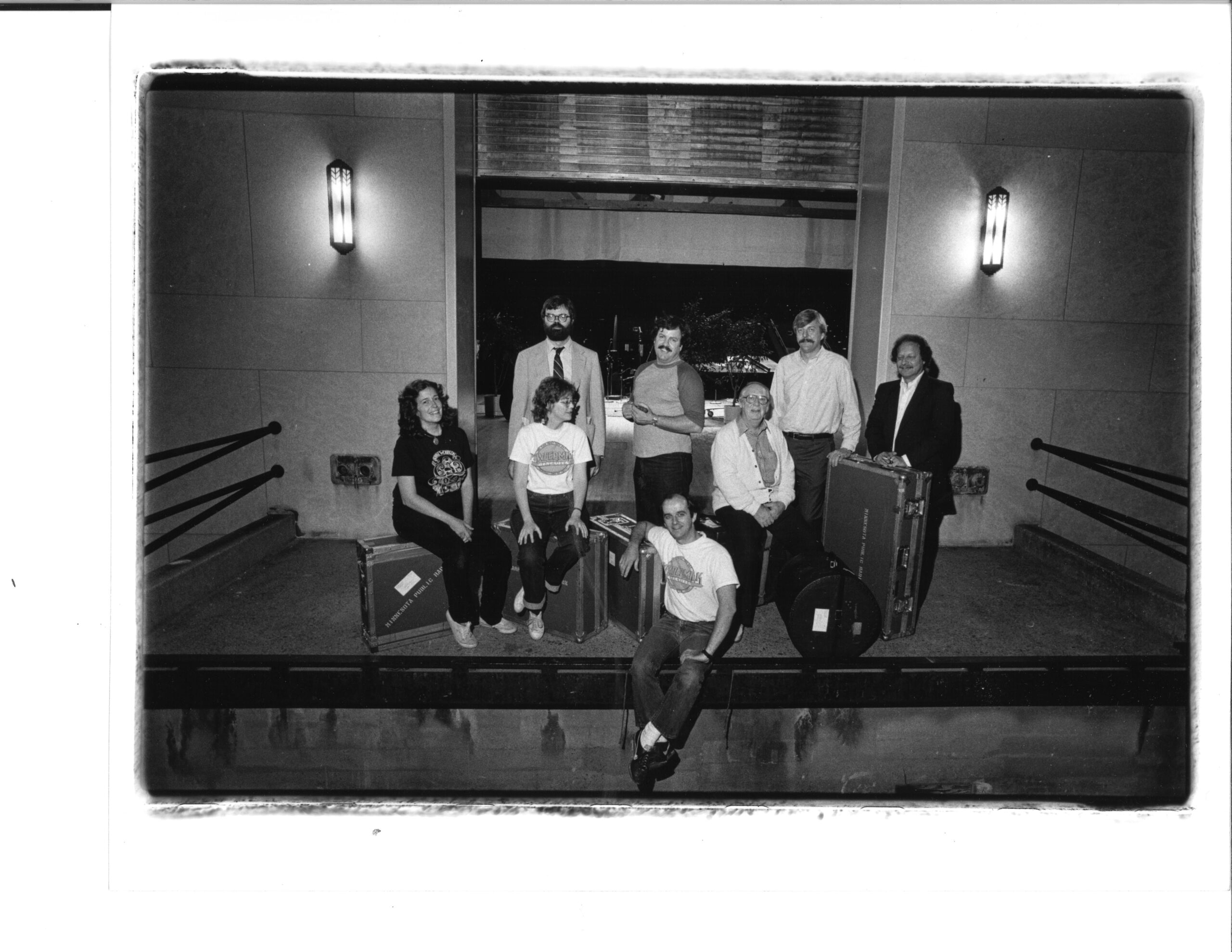

I recall early regular broadcasts of what became A Prairie Home Companion, when the show performed in an abandoned (at least I think it was) skyway between the Mears Park building in Saint Paul and the building next door. That space accommodated about 50 people. And thanks in no small part to producer Margaret Moos’s vision of the possibilities, the show kept going. Amazing.

After a nomadic tour of available, rentable auditoriums, the show made a deal with the Dworsky family to rent the World Theater, a movie house that had long been closed. Volunteers drained water out of the basement and scraped the gum off the seats. The rent was paid by the sale of popcorn and a sub-rental to a group that wanted to show Asian-language films on weeknights.

Once the show had matured and was airing locally every week, I got a call from my friend Don Forsling — who ran WOI radio, a powerhouse FM station in Ames, Iowa — asking if they could get tapes of the show and broadcast them in Iowa. We agreed and mailed them a tape each week. That was the beginning of Prairie Home’s “network.” By 1980, I had managed the plan to connect public stations by satellite and secured an “uplink” for MPR. APHC was then able to be transmitted live to stations across the country.

The problem with the national broadcasts was, as always, “cost.” I asked Frank Mankiewicz — then president of NPR — to fund APHC for national broadcast. He was very clear: “No.” And so we formed American Public Radio, a competing network, whose marquee program was A Prairie Home Companion, which had become an obvious success.

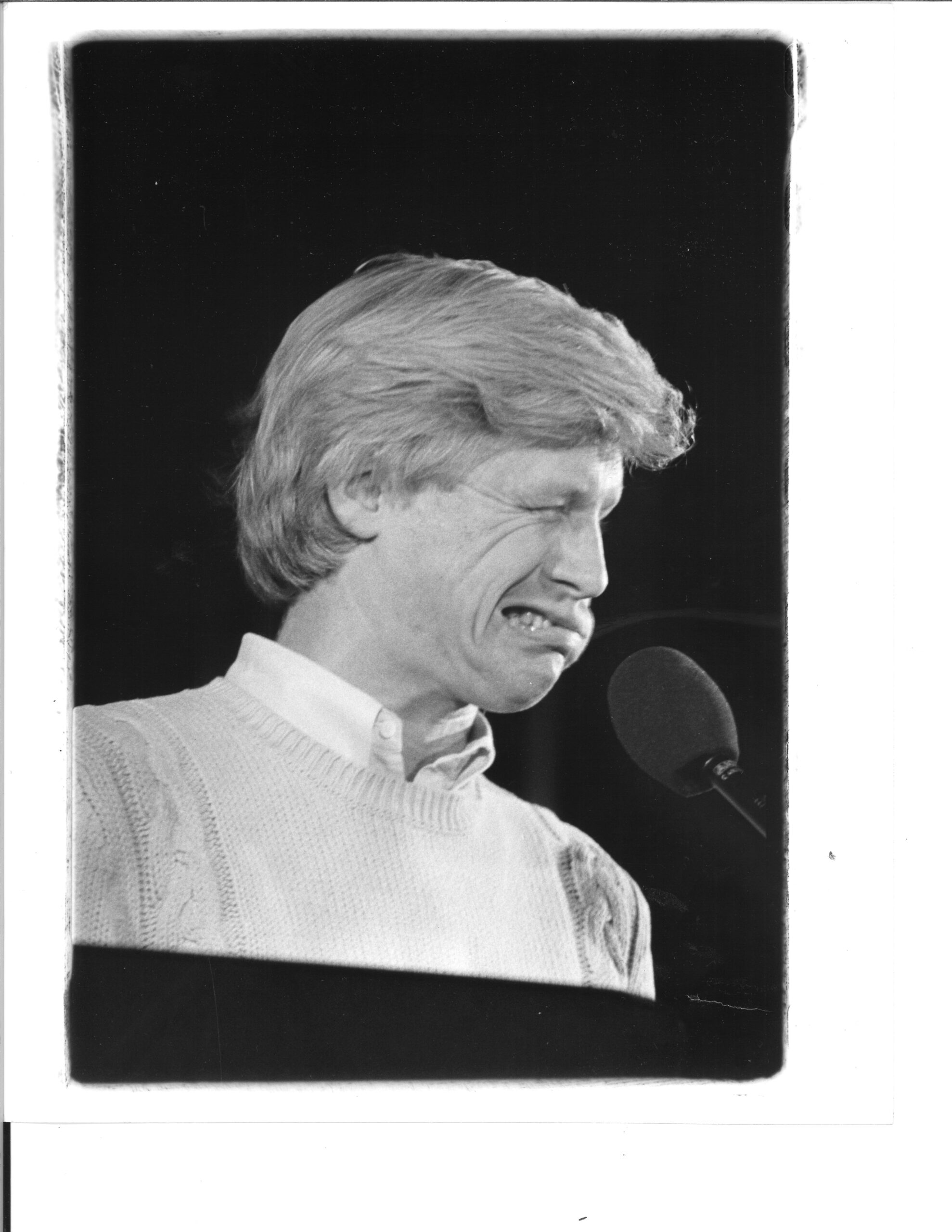

The 10th anniversary celebration show was held at the Orpheum Theatre in downtown Saint Paul, largely because the World Theater had been closed due to falling plaster and a variety of other infractions that the city felt were safety issues — and they probably were. Forty years later, that show — one of the very first for which we have video — still rings in my head. It was an amazing leap forward. Garrison outdid himself with the dancing salsa bottle and a group of similar characters onstage. The Orpheum was full, holding at least twice what the World Theater held in those days. Greg Brown summed it up: “It’s a fine thing you have done, Garrison Keillor.”

The Disney Channel shows added a whole new level of attention and complexity. They were televised with pretty basic production values. There really was no actual “set” and the World Theater’s stage looked bleak on television. But Disney loved it. Their ratings went way up. They marshaled their marketing department to bring media people to town and asked Garrison to talk with various reporters and writers — which he occasionally did.

The Disney broadcasts ended when Garrison decided to move to Denmark, and the “last show” broke all the rules. The program had never run beyond its two-hour time limit. Many public radio stations had skeleton staffs on Saturday nights and were unable to change their schedule, yet the show went on and on and on. The King Kamehameha Choir from Hawaii swayed onstage with flowered leis for everyone. The entire cast stood on the stage singing with the audience, which stood in a standing tribute and remained standing for the next 45 minutes. Seven p.m. came and went. At 7:10 the tech staff scrambled to get more satellite time and extended it until 7:30. At 7:30, the show continued. By that time Garrison was into “Good Night, Irene” and “Bye Bye, Love” and other farewell songs. The audience continued its standing ovation. Via teletype, the stations were advised that the broadcast would end at 7:30, and we ordered the playing of the American Public Radio audio logo signaling that the show was over. Except that on the Disney Channel it wasn’t over. They continued the broadcast for an additional 10 to 15 minutes. On Sunday morning, angry radio stations all around the country demanded that the Sunday rebroadcast include the extra time. And in some cases, a special feed of the additional segment was sent out to be patched onto the end of the rerun. It was clear that nobody — Garrison included — wanted the show to end.

And as we all now know, it shouldn’t have ended.

Over the summer that followed, I spent a lot of time at a lake house in northern Minnesota where the nights were warm and the loons were calling. I would often email Garrison, setting the scene as nostalgically as possible, making every attempt to make him homesick. I later learned that I didn’t have to try that hard. He wasn’t funny in Danish and was already homesick. Finally he responded, saying, “Maybe we could do it again,”

Garrison returned to the U.S., but to New York, where he worked out of his small office in the New Yorker building. I went to visit him one day and talked about a return, doing a big show, bigger than anything we had tried before, and he liked the idea. We were walking along Sixth Avenue talking about venues for a big, big show. We found ourselves standing under the marquee of Radio City Music Hall, and it hit like bolt of lightning: That was the answer.

We explored Radio City with the theater manager, who explained to us how the stage could rise up from the basement and rotate like a railroad roundhouse. And he described a variety of other incredible special effects.

Garrison scheduled three shows at the storied 6,000-seat venue: Friday, a Saturday matinee, and Saturday night, with Saturday night being a national APR radio broadcast. The Disney Channel was back on board too.

The Everly Brothers came as did Chet Atkins and a host of other great talent. We hired a Hollywood production crew. And true to form, Garrison embraced it all, with the Everly Brothers singing while rising up on the rotating stage in a 1957 Chevrolet convertible. Three sold-out shows. Some 18,000 ticket holders. A smashingly successful “return” for Garrison and a big boost for public radio and the Disney Channel.

Of course it wasn’t always that simple. Back in the early days, Garrison and I argued incessantly, each of us taking a polar opposite position. If I said black, he’d say white. (In fact, it was probably neither.) But we were a good team. What he did I could not do; what I did he could not do. And often in between us was Margret Moos, the diplomat facing two immovable objects.

As the nascent radio show grew in popularity so did its live audience. I loved the ticketing system that Margaret and Marge Ostroushko and others developed at the beginning (long before Ticketmaster existed). The World Theater seated about 900 people at best and in those early days even fewer. People from all across the country wanted to come to the shows. If you mailed in a ticket request, you got a blue card back telling you that you couldn’t get a seat — but the next time you wanted to come, use the blue card and it would give you a higher priority. And people did and then they got a red card, and finally on the third try a green card that gave them a seat. But some didn’t wait for that process to play out: they simply drove, flew, hitchhiked to Saint Paul and stood in line outside the theater hoping to grab a last-minute seat. I felt so bad that people had come from everywhere to stand in line for a show that they could not get into. And in a few cases, where I thought it was absolutely unacceptable not to get them in, I would invite them into the theater and find a place where they could stand or sit on a stairstep. They were so incredibly grateful. I’ll never forget it.

LINDA WILLIAMS, SINGER, SONGWRITER, PERFORMER (ROBIN AND LINDA WILLIAMS)

We were sitting on the front porch at GK’s house after a show and hanging around for the show a weekend later. He came up with the idea of our doing a record pitch commercial — fast hard-hitting bluegrass snippets of Broadway songs that were not in any way connected with common themes from country or bluegrass. He said to do songs from West Side Story or other musicals but nothing from, say, Oklahoma, shows that leaned country. We’d do them as fast as we could, playing and singing harmony. That led to Marvin and Mavis Smiley and the Manhattan Valley Boys.

Smiley is a big name in Augusta County, Virginia, where we live, so we used that last name, and he most likely added the first names and the Manhattan Valley Boys. We continued to be asked to bring back Marvin and Mavis many times over the years, sometimes with other themes, like Down Home Diva with bluegrass snippets of familiar opera arias.

It was always very hard to get through a Marvin and Mavis segment without us breaking into laughter. We used to get lots of requests to do that in concert, which was impossible to do without the band, especially the drummer.

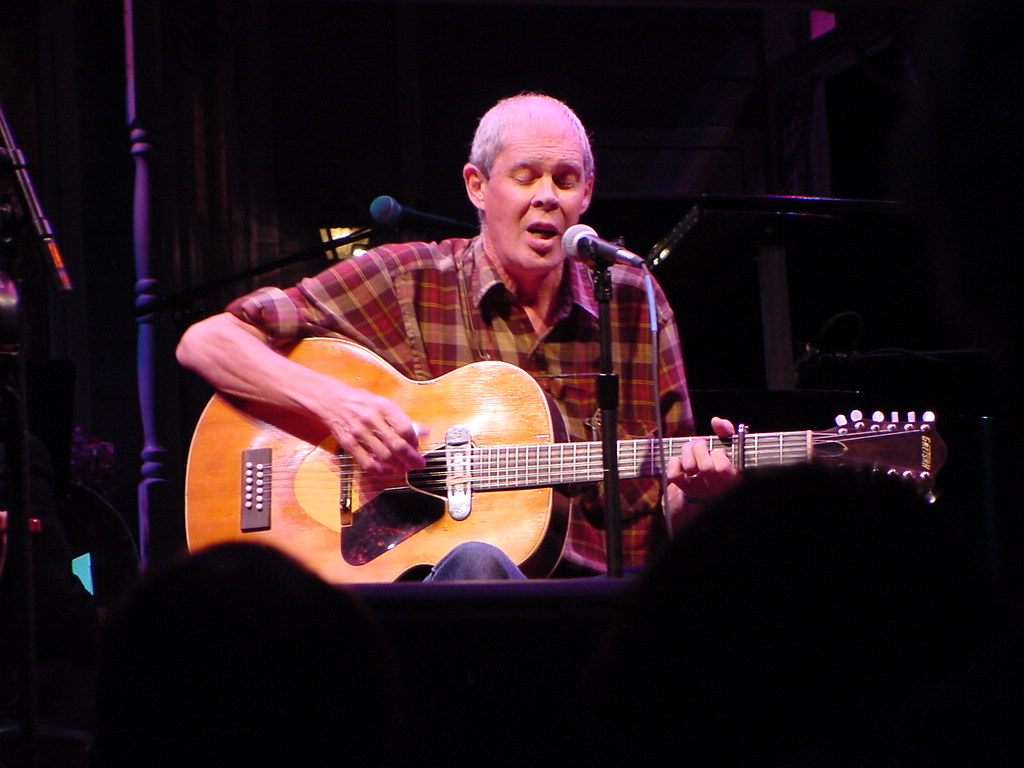

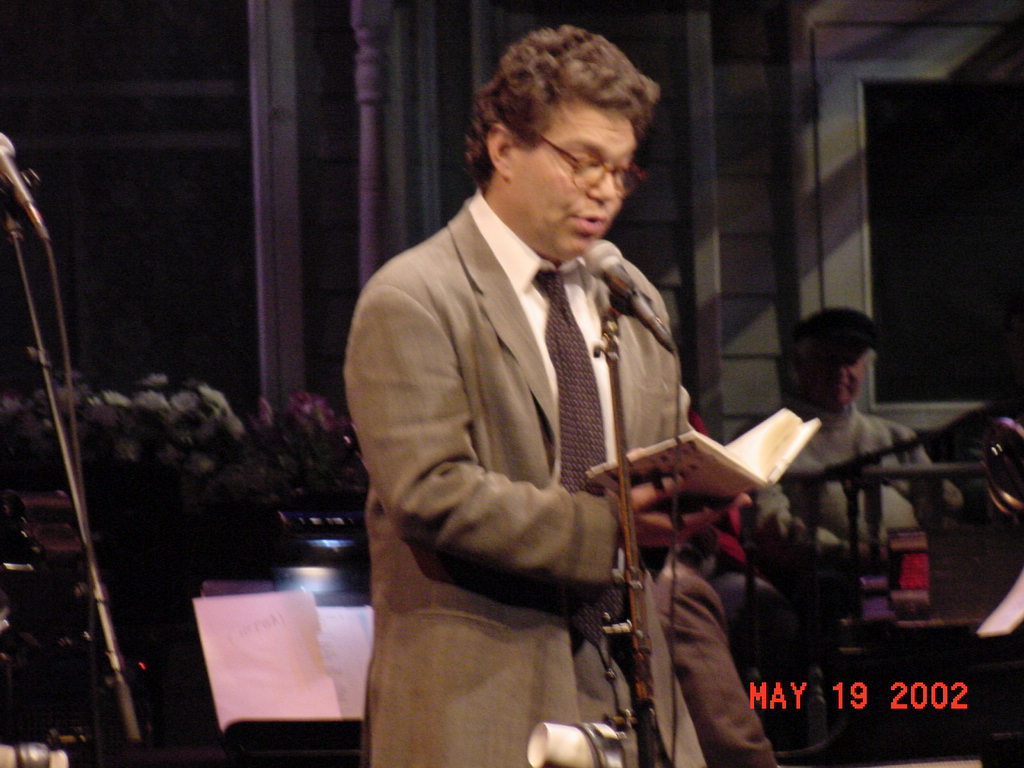

TOM LIEBERMAN, GUITARIST, SINGER, SONGWRITER

A few of my more lucid memories of my years on APHC, for the record:

1976

My good fortune to meet Garrison Keillor was due to my good fortune of having been a part of the vibrant music scene of the Minneapolis West Bank neighborhood in the mid-’70s. I had started playing my original songs at the Coffeehouse Extempore while still in high school, and there found myself in the orbit of such mentors as Sean Blackburn, Dakota Dave Hull, Bob Douglas, Bill Hinkley, Judy Larson, Mary DuShane, Charlie Maguire, Pop Wagner, Bob Bovee, Stevie Beck, Scott Alarik, Maureen McElderry, Tim Hennessy, Peter Ostroushko, Jerry Rau, and countless others. In the mid 1970s, many or most of these folks had found their way onto Garrison’s nascent radio program as performers, and eventually, he got around to meeting me.

I was invited to meet Garrison in 1976 at the old MPR offices in the Park Square Court Building in Lowertown Saint Paul. His “office” was a converted closet wedged under a stairway. It had no window, of course, but I do remember that it had the smell of disinfectant and a sense of dread. As I entered, I perceived a large figure seated deep in the murky darkness behind a Luxo lamp, which was aimed squarely at me, and I extended my hand toward it. The silhouette extended its hand and shook mine. It then introduced itself as Garrison Keillor.

Coming from a “radio family,” I already had a pretty deep understanding and appreciation for the program and story world that Garrison was building. My father’s mother, Julia, had been a juvenile “sweet” singer in the ’20s. She partnered with a young man named Julian to become “Julie and Julie,” who were singing sweethearts on the early airwaves of KSTP and WCCO. So, although I was a 19-year-old upstart, much of what Garrison and I discussed in that first meeting made a lot of sense to me.

He invited me onto the show to sing some of my original songs, and that turned into several years of semi-regular appearances on APHC as a solo artist, a member of the vocal trio Rio Nido (with Tim Sparks and Prudence Johnson), and as a utility guitarist/vocalist/voice actor wherever needed. I was particularly proud to be the voice of the eponymous “El Muchacho Alegre” of “El Muchacho Alegre (Happy Boy) Hot Sauce.” Over these years, I was also invited to develop special material and segments for the show, and I had the opportunity to work on the production staff, as the show’s cultural footprint expanded.

Early ’80s

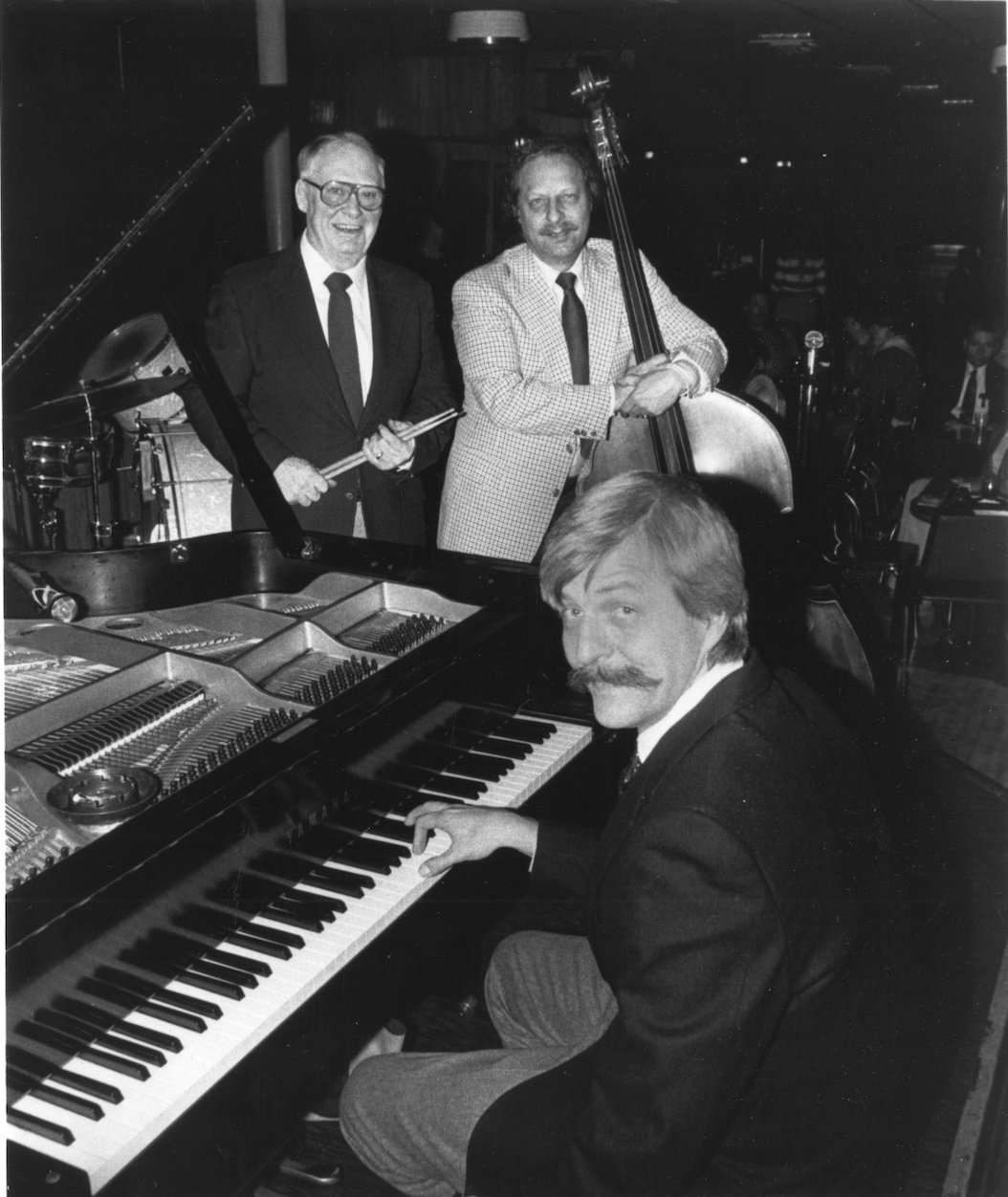

After leaving Rio Nido in 1979, I spent most of 1980 traveling abroad, looking for a new city and a new scene. However, when I returned to Minnesota in the later part of that year, Garrison had ousted one house band, and brought on another — The Butch Thompson Trio. This was somewhat fortuitous for me as a singer and guitarist, since I was a natural fourth for Butch’s trio. Butch and I had been friends and frequent collaborators, and I was friendly with his bassist, Bill Evans, and drummer, Red Maddock, from the traditional New Orleans music scene at the Hall Brothers Emporium of Jazz. Our styles of music meshed well with one another, and I was happy to receive a call to be on the show most weeks in 1981. Of course, I understood that the show was booked one week at a time, and I knew better than to ever expect that the call would keep coming. But I was always happy to get it when it came.

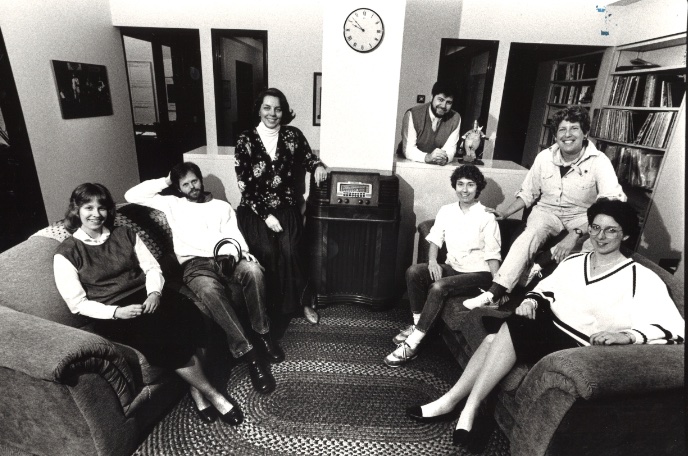

As impressed as I was by Garrison’s talent, I was equally impressed by the support system that had been built around him and the show. His producer, Margaret Moos, ran the show with a firm hand, and by watching her work, I began to develop an understanding of what a producer actually does. I recall one particular Friday rehearsal when I was behaving particularly squirrely, and Margaret impressed upon me that a rehearsal was every bit as important as a show and should be taken as seriously. Margaret, Garrison, and the rest of the staff and crew taught me a lot about what it means to be a professional.

Even though the show now had a national audience, it was still a pretty low-rent touring operation. I remember one road trip where we were playing shows in the towns of Marshall and Minneota in western Minnesota. Garrison drove the Winnebago full of musicians, and there was an equipment van being driven by the crew. We’d pull up to the high school auditorium and load in the gear for the show. I specifically remember Garrison putting a pot roast into the oven of the motor home prior to one of the shows, and us returning to the motor home to enjoy it afterward. We then played a little bit of poker, before retiring to our shared rooms in the local motel. My roomie was Tom Keith (aka Jim Ed Poole), and he appreciated none of my inebriated hijinks. Go figure.

Tenth Anniversary

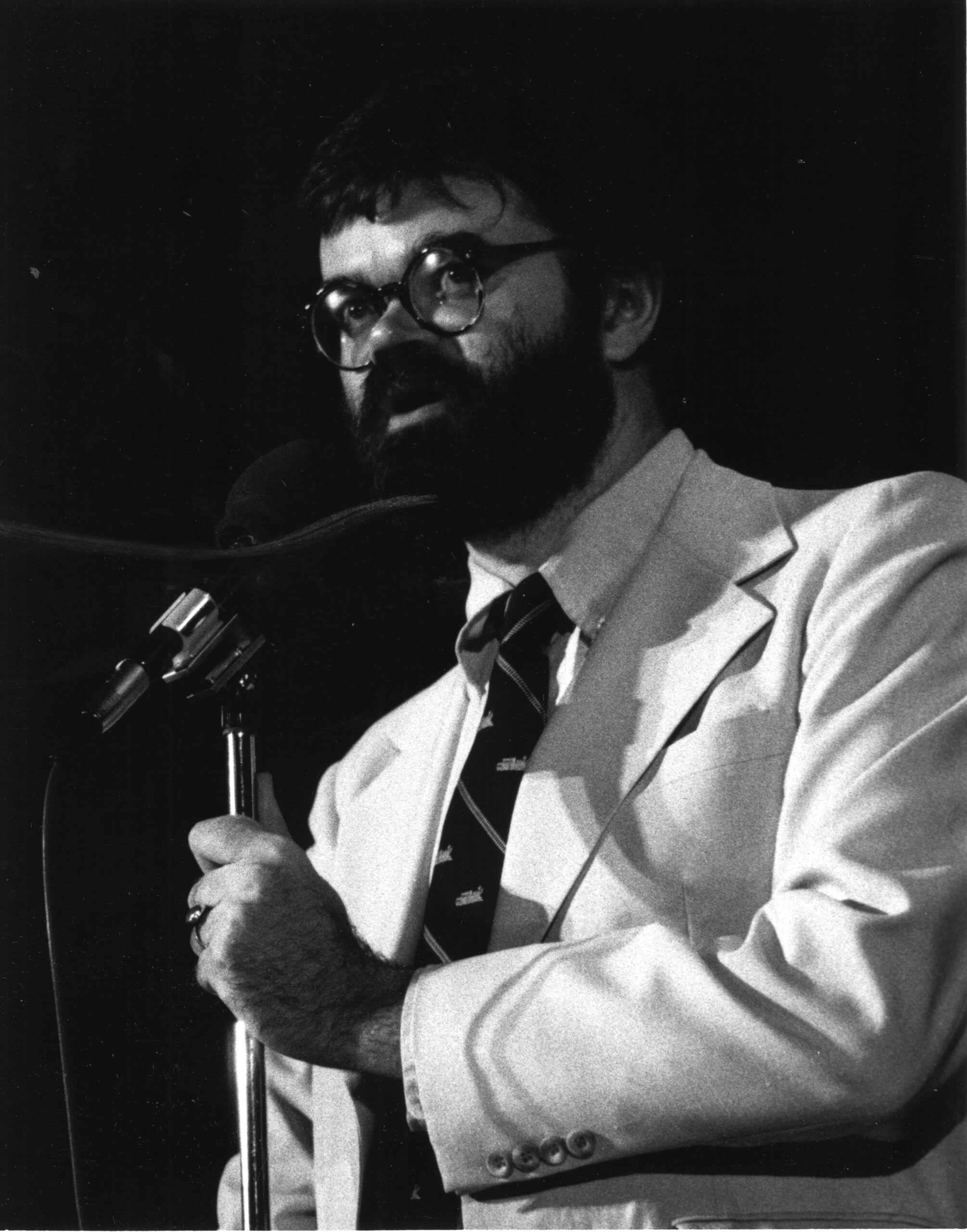

When the 10th Anniversary show rolled around, I appeared on that show with the vocal trio “Lieberman, Fogel, and Bey” (with Arne Fogel and Turhan Bey), singing the song “100 Years from Today.” I recall that we also performed a commercial for bananas, while wearing flouncy banana sleeves that did nothing to improve my guitar playing. The post-show celebration was held outdoors on the grounds of the State Capitol on a portable stage, and I had the honor of serving as the MC of that show. It was a true celebration and a blast.

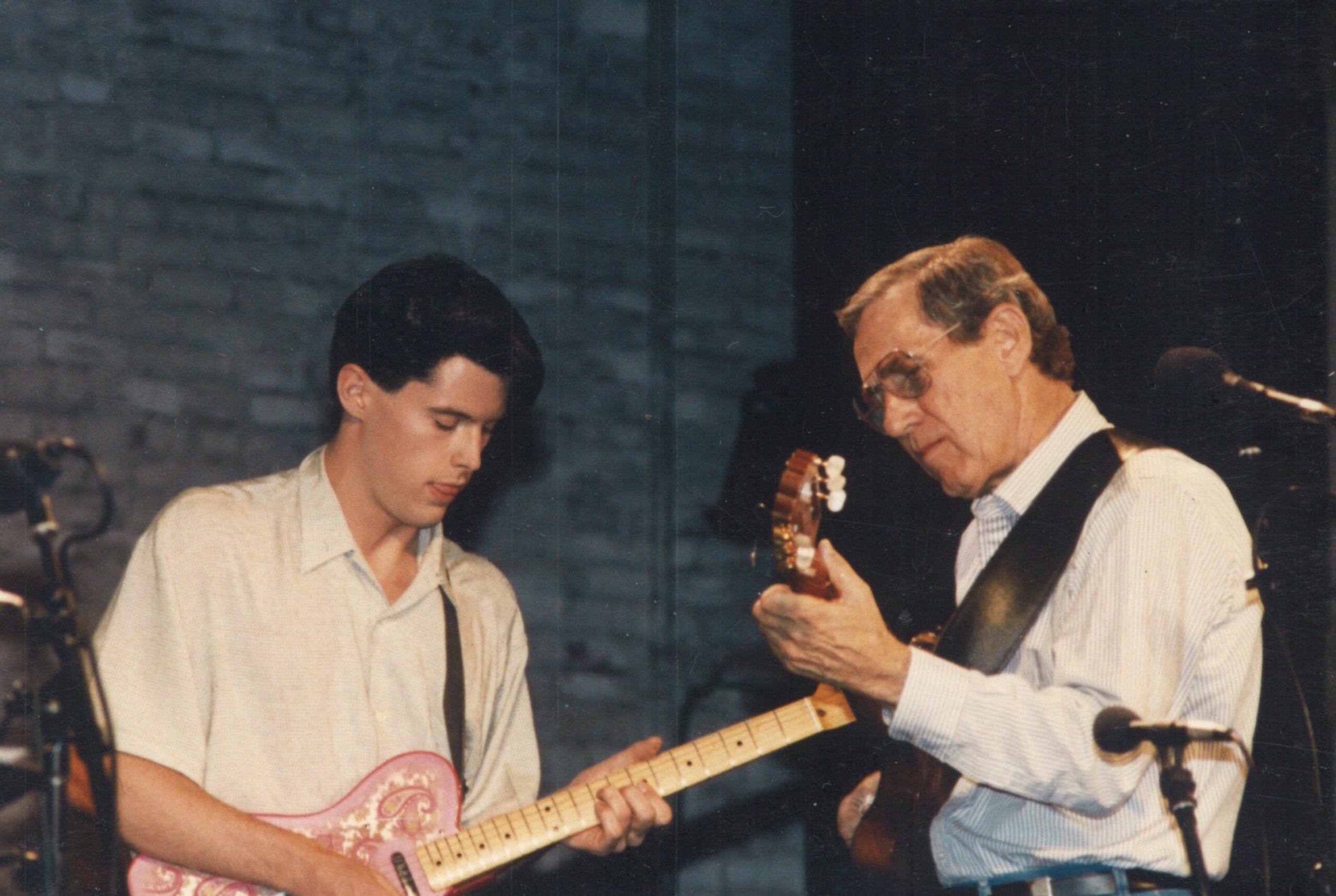

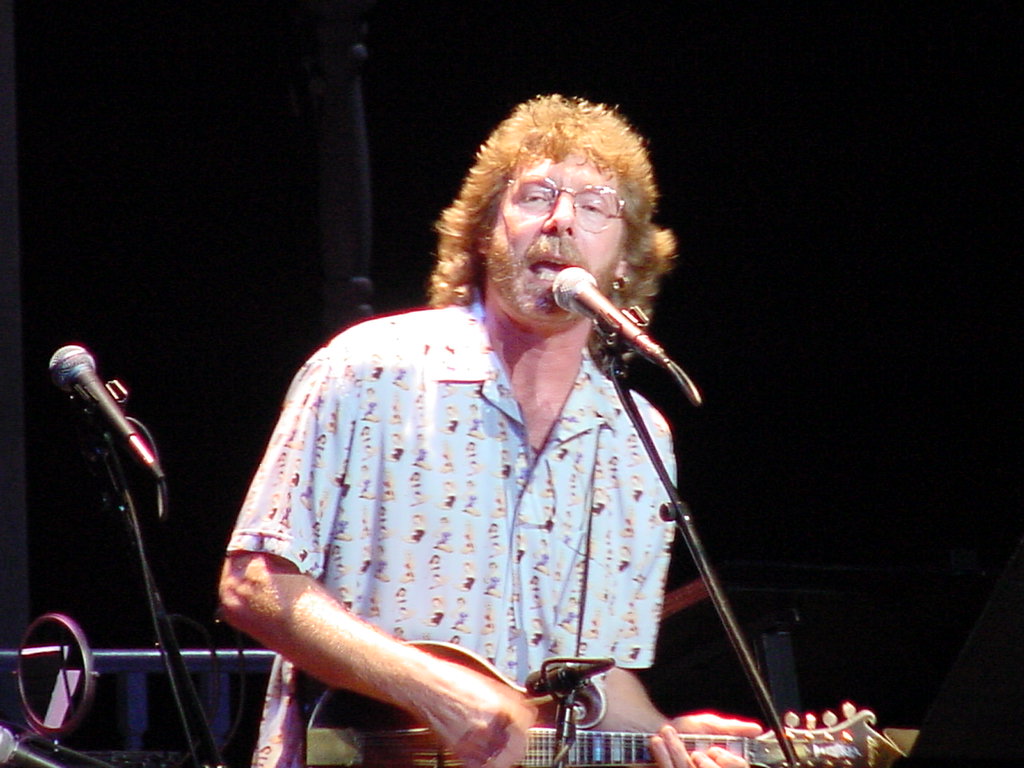

Chet

Ultimately, my best AND worst moments as a professional guitarist happened at the same time when, while tuning up before a show (and feeling perhaps a bit too secure in my position), I was tapped on the shoulder by associate producer Marge Ostroushko, who “asked” if I could please get up so that “Chet could sit down.” I looked up, slowly, and there he was, the Country Gentleman himself. Chet, understanding the gravity of the moment, seemed apologetic, but I simply offered him my chair, and asked if I could get him a cold drink or something. I understood, of course, that the highest compliment any guitarist could receive was to be replaced by “Mr. Guitar,” Chet Atkins, and that it would never get any better than that for me, so I dedicated myself to cobbling together a livelihood in the creative and production industries.

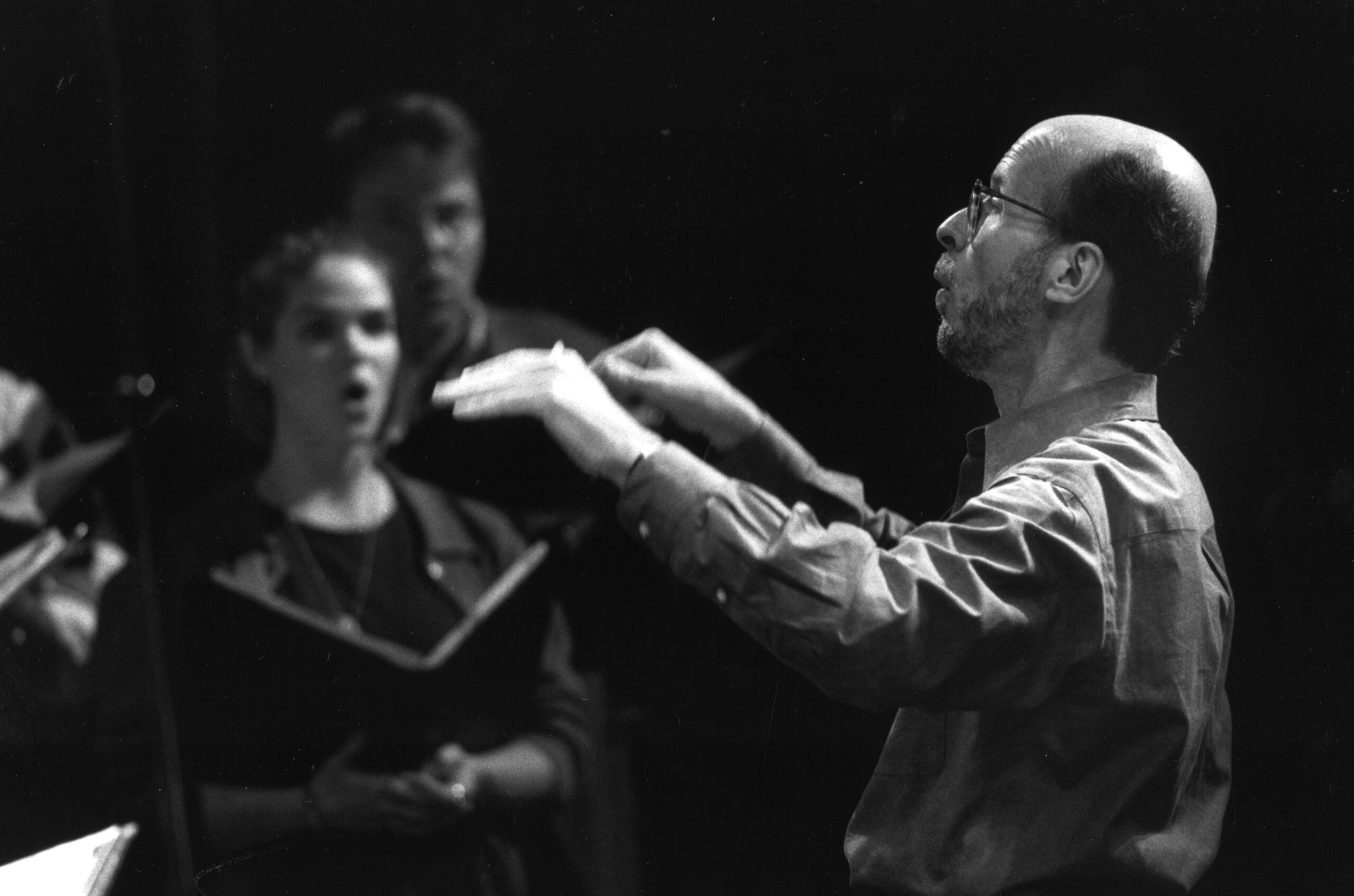

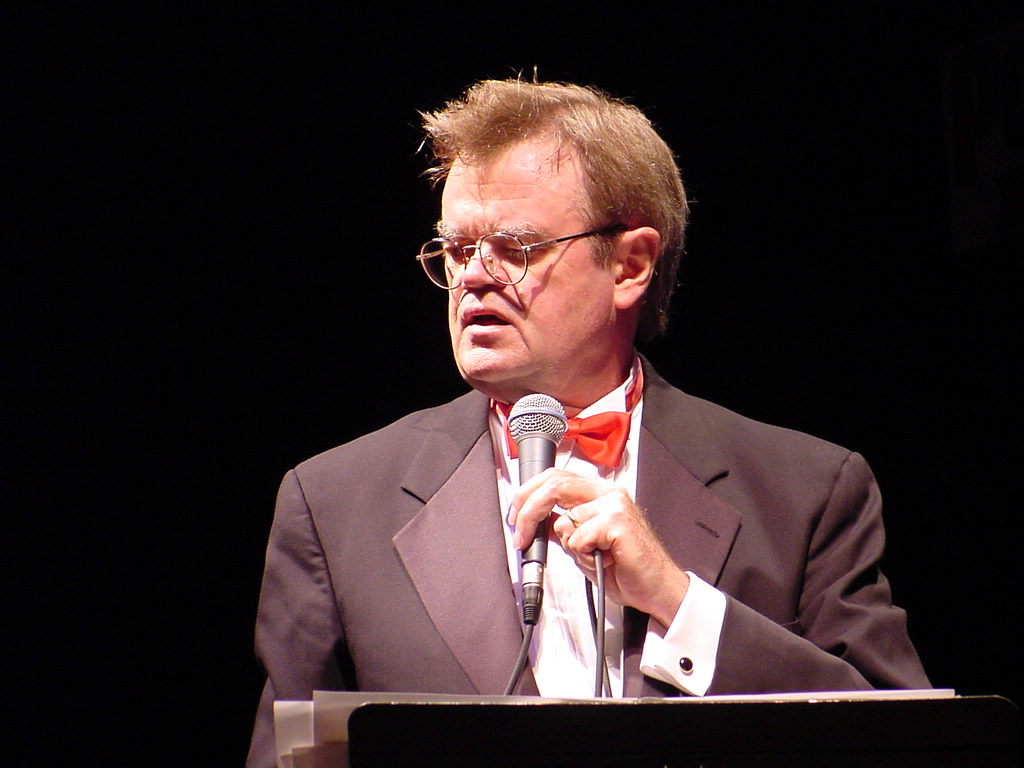

PHILIP BRUNELLE, ARTISTIC DIRECTOR AND FOUNDER OF VOCALESSENCE, AND INTERNATIONALLY RENOWNED CONDUCTOR

My first show

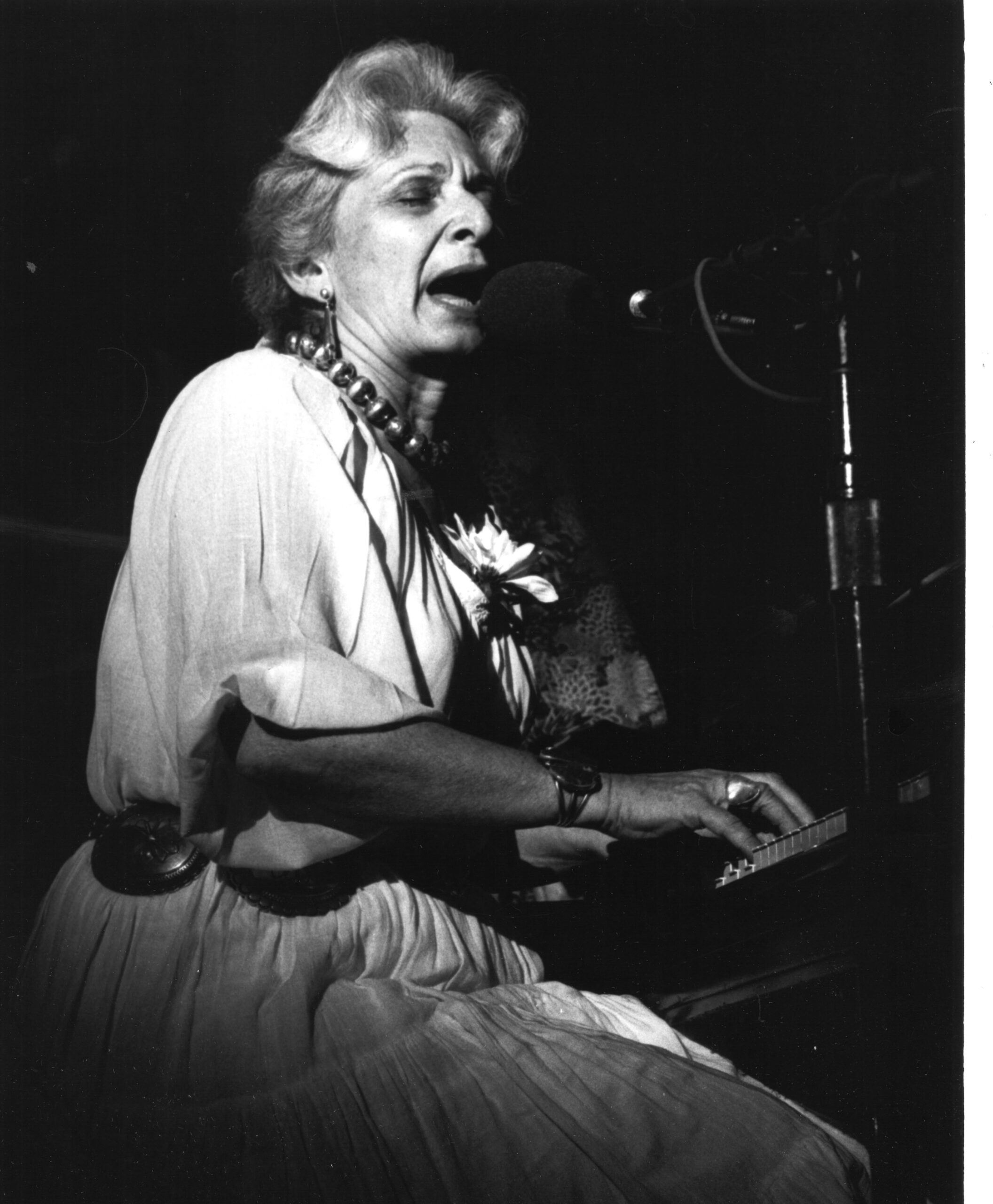

Garrison called me and said he was going to start a radio program and wanted someone to play piano — someone who could play classical music and hymns. I told him that I could do that; he asked if I knew a lot of hymns. I told him that every hymn he knew … I knew. And the question would be: who knew more verses? (The answer was me.) So I showed up for the first show, playing on an upright piano. I stayed with the show for a while but knew that with my work at Minnesota Opera and VocalEssence, I couldn’t be there every week, and so Butch Thompson took over.

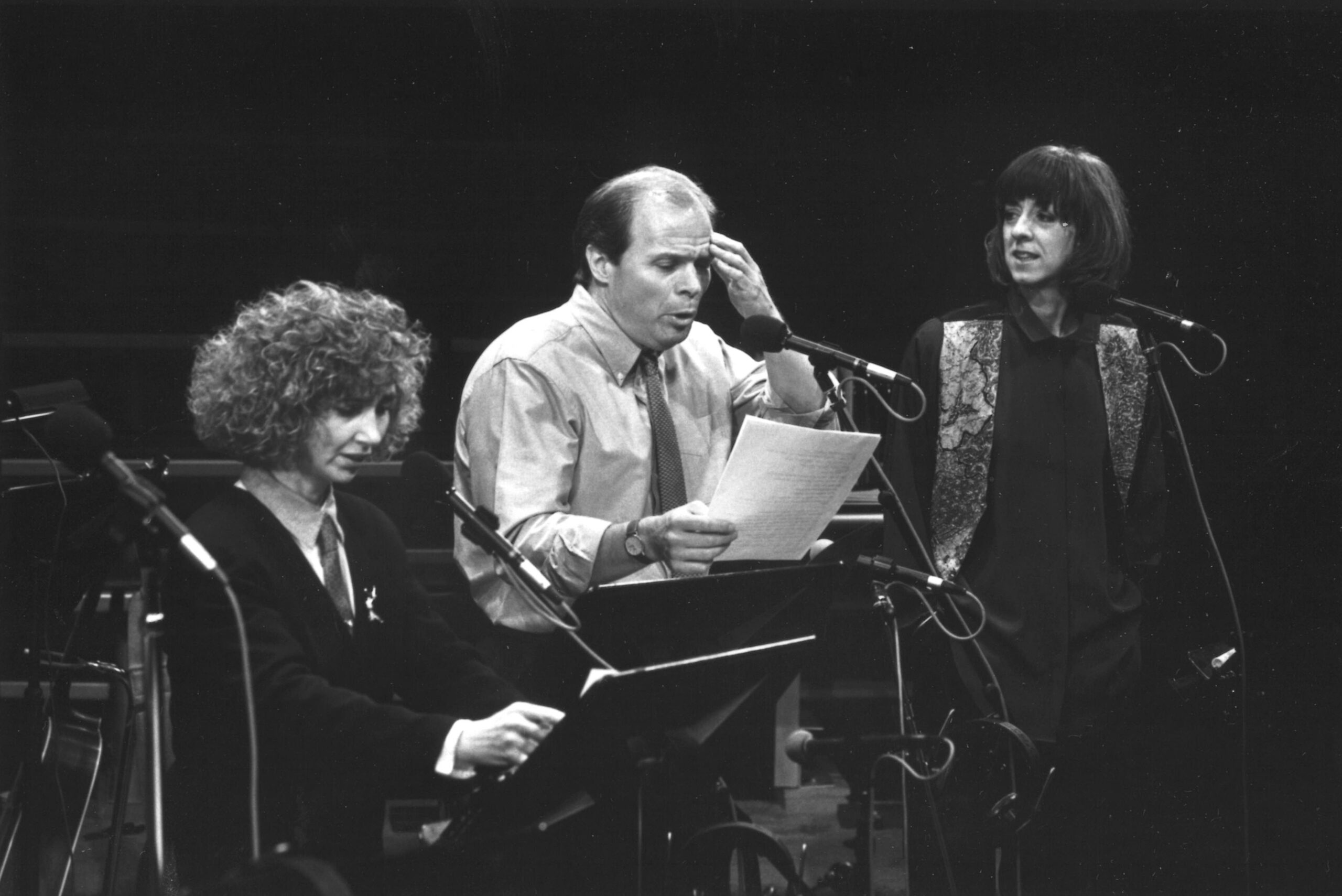

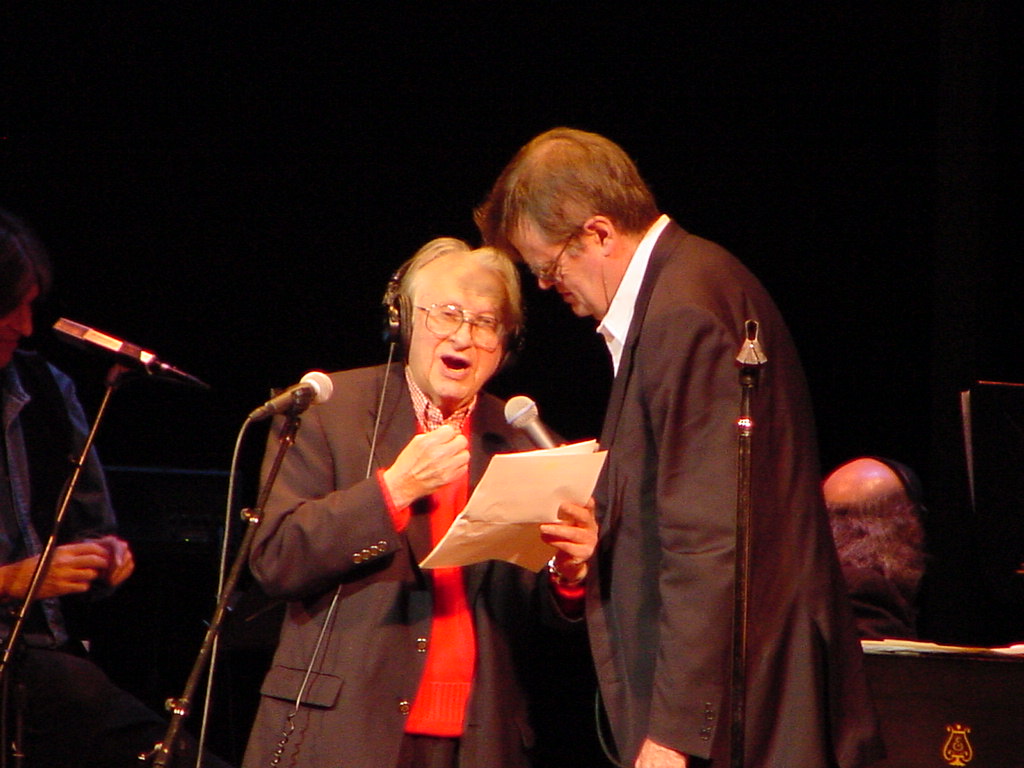

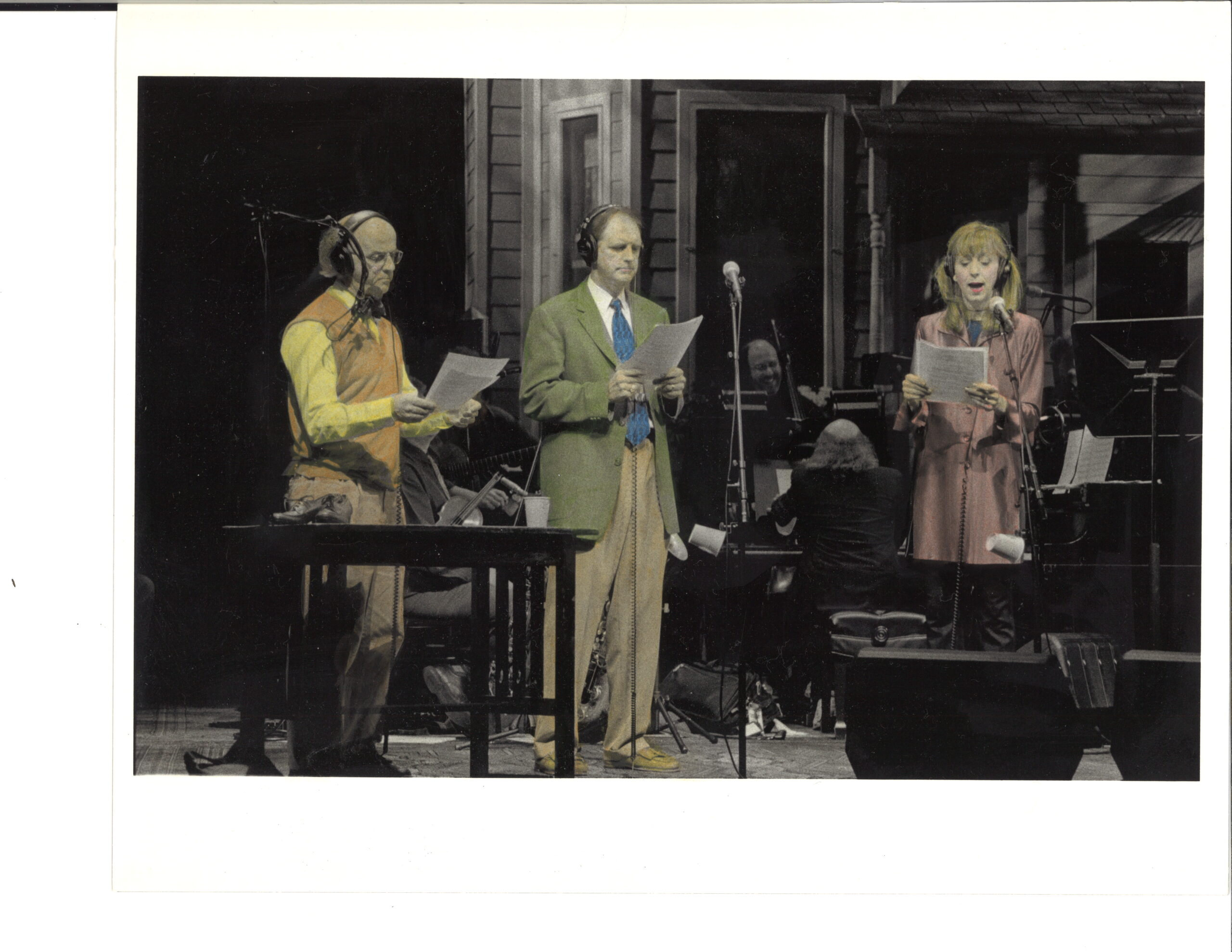

The Thanksgiving Cantatas

When GK decided to have Vern [Sutton}, Janis [Hardy], and me create these cantatas (improvised from audience suggestions), we knew we could do it because all three of us could wing it. We got all the slips of paper from the audience and went to the basement, which in those days WAS FREEZING! We separated all the suggestions into categories and decided on themes for what would become “I am thankful.” I typed up our lists (we were under a BIG time crunch since the cantata was on the final half hour of the show) and we performed. Not sure how many years this happened.

Rudolphus rubrinasus

On one December show, I was standing backstage and GK came off and said we were two minutes shy and did anyone have a short holiday song. I told him I could sing “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” in Latin, and he said GO! I went out and sang it, accompanying myself, and dedicated it to my high school Latin teacher, Evangeline Peterson. (She was not listening that day but heard about it later and was THRILLED that her name was mentioned on public radio!)

Freckles

The only time that I saw GK lose it was when Janis Hardy came onstage with her dog Freckles and sang “Indian Love Call.” Janis walked out with Freckles, the audience exploded in laughter, of course. Janis knelt down next to the dog and started singing “When I’m calling you.” Freckles liked to howl when he heard Janis singing, and the combination of hearing Janis sing and Freckles howl caused GK to start laughing. He had to leave the stage.

VocalEssence

Among the many, many appearances of the VocalEssence Ensemble Singers on PHC, one of the most memorable was when the Ensemble Singers sang “El Hambo,” a song by the Finnish composer Jaakko Mäntyjärvi that is in nonsense syllables. GK decided that, rather than singing it straight through, we would sing a few measures and then he (or Jim Ed Poole) would give a made-up translation, which brought the audience into hysterics.

JANIS HARDY, SOPRANO

Like Garrison, I can’t remember a lot of specifics about those early days — more impressions than complete scenes. For instance, it seemed to me that every time I performed on a show in the tiny theater of the Arts and Science Center in Saint Paul, there was always a baby crying or child yelling! I also remember, with Philip and Vern, frantically trying to put together the Thanksgiving Oratorio based upon suggestions from the audience — downstairs at the Fitz with pieces of paper flying everywhere — doing it all in under half an hour, as I recall. It was also not unusual for Garrison to throw an improv scenario at us (Vern, Philip, and me) and we’d take it from there — singing an opera scene at the drop of a hat! Scary but fun!

There was a period in my life where I inherited a bakery and spent most of my waking hours there. So I often came to the show dressed in flour-covered overalls. And I’m not exaggerating! Garrison would take that opportunity to describe to the radio audience the beautiful gown I was wearing, much to the amusement of the theater audience. And yes, I’m sure Philip can regale you with the story of Vern and me singing a duet with my dog Freckles. Pretty hysterical.

We loved standing in the wings watching Garrison and Tom and Sue and Tim do their magic — priceless! It was a magical time and I’ll be forever grateful.

CHARLIE MAGUIRE, SINGER-SONGWRITER

Spaghetti in Saint Paul, 1974

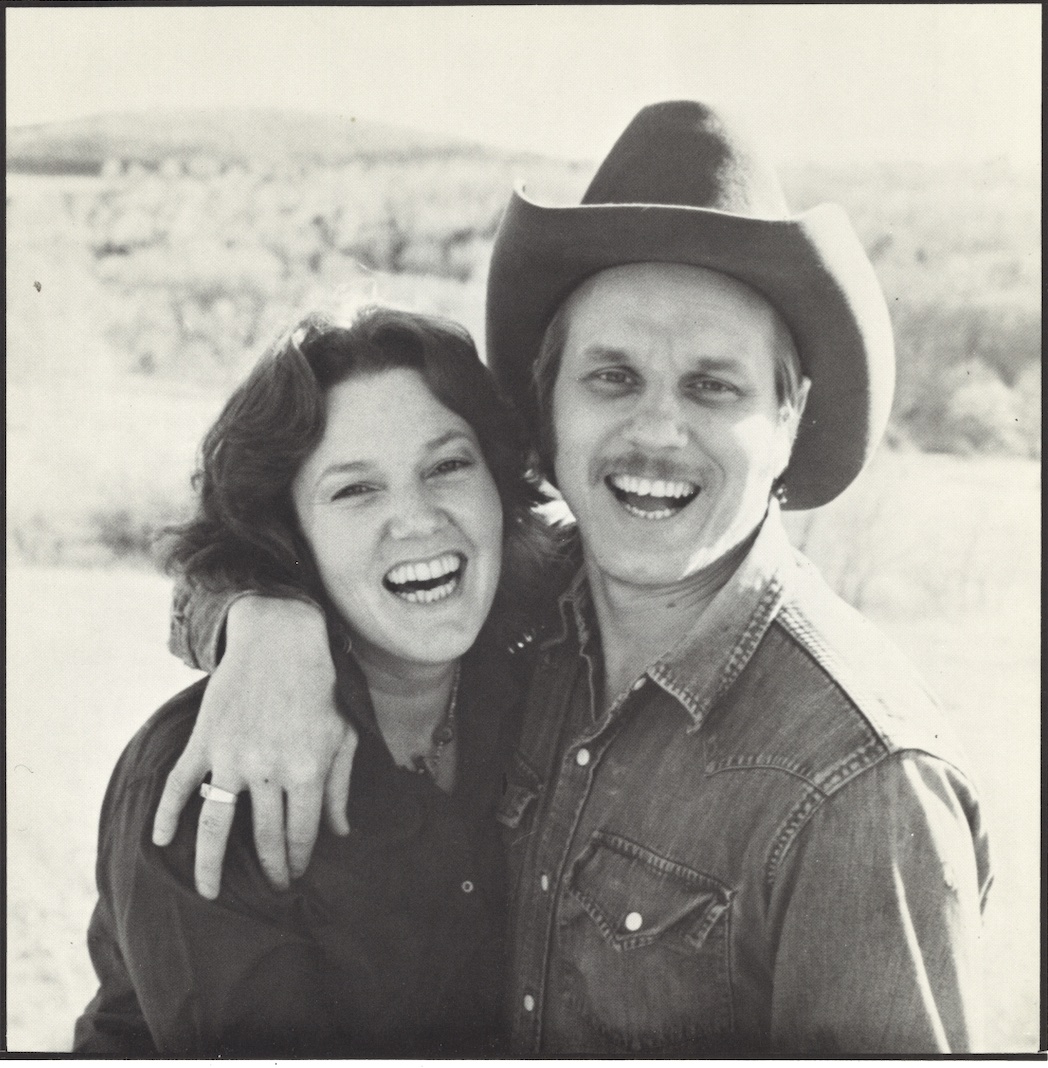

Returning to Minneapolis from 14 months doing national service (VISTA/Western Nebraska) in the fall of 1974, I got a call from fellow performers Bill Hinkley and Judy Larson that a writer and radio DJ named Garrison Keillor had just started a variety radio show, based in part on the Grand Ole Opry. They both knew my music — like “Getting in the Cows” and “Winter on the Farm.” The songs had a rural theme that Garrison was after at the time, and Bill and Judy pitched me to Garrison thinking I might be a good fit. He invited me and my wife to dinner at his house for spaghetti, and afterward, hearing a few of my songs clinched the deal. I was a featured guest on the second or third broadcast, and a fairly regular performer for years after.

Sweeping up and eating up … together

When performers remember APHC, it’s the early years they seem to recall with the most warmth. It was community in the truest sense. We’d all — Garrison included — sweep up the theaters after a show, then adjourn to La Cucaracha, the local Mexican restaurant, for a late dinner together.

Born-in-a-trunk daughter makes APHC appearance at 11 months

During the early shows, the “green room” was simply backstage behind a curtain. Local performers brought their children (who could afford a babysitter?) who mingled like an extended family. On one show, Garrison invited the Persuasions who happened to be on tour through town. The quartet — too long on the road — were missing their own families. One of the members scooped up my 11-month-old daughter, Elsie, into his arms and took her out in front of the audience for the finale. Elsie put her little arm around the singer’s neck as if he was a long-lost uncle, and quietly sucked her thumb as the Persuasions smiled and laughed at her and went into their final song.

The Morning Show — APHC incubator

People may not know that Garrison was on the air not only on Saturdays but also worked Monday through Friday from 6 a.m. to 9 a.m. on Minnesota Public Radio in Saint Paul. I loved being on the show in the mornings, since it was just Garrison, engineer Tom Keith, Bob Potter, who read the news, and me. I often used that time to work up new material for my tours and used APHC and The Morning Show to test things out. If Garrison heard a new song he really liked, he’d ask me to come on the show the following Saturday and sing it. That’s how a lot of my songs came into being. “DM&IR” is about a railroad on the Iron Range of Minnesota; “Talking Home Improvement,” about the perils of making your own home repairs; “Oh Cold & Misery,” about starting your car on a cold Minnesota winter morning; and lots and lots of others.

Spontaneous, no rehearsal necessary

One time on The Morning Show, a retired guy who loved to write poetry about his childhood, sent in a piece to Garrison titled “The Evening Train.” In it he painted a picture of his days as a kid going down to the railroad station to see who was getting on and off in his little town of Cokato, Minnesota. So Garrison, Tom, and I, were sitting there at the mics in the MPR Studio, and during one of Bob’s newscasts (when we could talk without being heard on air), Garrison turned to me and said, “Tell you what, I think this poem would make a good song this week on the show. Why don’t you go into the hallway and set it to music, and then try it out in the 8:30 segment?” I have always been fast with the music to a song having studied Woody Guthrie, and Carlton Lee’s poem was so songlike, I had it ready in 15 minutes flat.

On a book tour with guitar, spoons, and new friends

Sometimes there was “APHC” work to be had without actually being on the air. Out of APHC’s “Department of Folk Song” came a book by Jon and Marcia Pankake titled A Prairie Home Companion Folk Song Book. It was a full-sized hardcover published by Viking Press with a foreword by Garrison — released in the fall of 1988. Viking hired me to go out on the road with the authors and we sang songs from the book at store signings. We had a ton of stops all over the place. There were a lot more independent bookstores in those days, and as we wore into tour, I taught Marcia how to play wooden spoons in rhythmic accompaniment to the songs we sang. It was the beginning of a friendship that lasts to this day.

On experiencing Vietnam via Omaha

I credit Garrison and APHC for my start in Minnesota as a songwriter/performer. Getting on the show on a regular basis often led to other well-paying gigs around the region for anyone who wanted to travel to an audience that wanted a bit of the show in their own backyard. A request for me came in from a law firm in Nebraska. The day before Thanksgiving that year, I flew down to Omaha with my little Martin Terz guitar that fit easily in the overhead compartment of the airplane, and upon landing was promptly chauffeured to a holiday party. I had a great time with that little guitar in the law library, surrounded by people who loved the songs they had heard me sing on the show. Between sets, one of the lawyers came up to me with a request I thought unusual for his line of work: it was for traditional folksongs Joan Baez had recorded. I sang as many of the old ballads as I could remember, and this guy filled in beautifully with a soft voice right on key. He introduced himself as William Holland and then proceeded to tell me that he would listen to Baez while piloting a Huey helicopter in Vietnam. Holland told me story after story about the war, and later put many of them into a novel titled, Let A Soldier Die (Delacorte Press). The longer I was on the show, I realized that APHC was not only entertainment for many, but also a way for some to find peace in their lives. Music, as they say, is medicine. And as the show endeared itself to more and more listeners, I think that many were eased by Garrison’s stories — and the way a good song can go straight to the heart.

“It Seems We Met Somewhere Before …”

Looking back, I like to think that we took our work and our music seriously, but not ourselves. That was partly the secret to the early success of the show. The beginnings of A Prairie Home Companion grew out of the West Bank folk scene that passed for Greenwich Village around Minneapolis in the 1970s. We had a lot of good times, comradery, and encouragement, and got to share our songs and the music we loved with the world.

ANDRA SUCHY, SINGER

One of my favorite recollections is the time I was in the car with GK, goinh from the hotel in Nashville to the Ryman. GK asked if I had ever been to the Country Music Hall of Fame Museum. I had not, so he looked at his watch, gave me a twenty dollar bill and had the car drop me off. He said, “You can be an hour and a half late to rehearsal. I know the boss. Come over after you get through.” I’ll never forget that!

Another memory is being on the tour bus and making cheese curds in the middle of the night in the microwave, which I had no idea was the proper way to eat them (not cold right out of the bag).

Or when we did a show in Bismarck and I suggested rewriting the words to an old cowboy song (come a ti-yi-yippee, etc.). He said, “OK! Be back with it in 20 minutes!” Keep in mind, my idea was for HIM to write it. The muses were good to me that day because I came back with “The Old Suchy Trail” and it made it on the show.

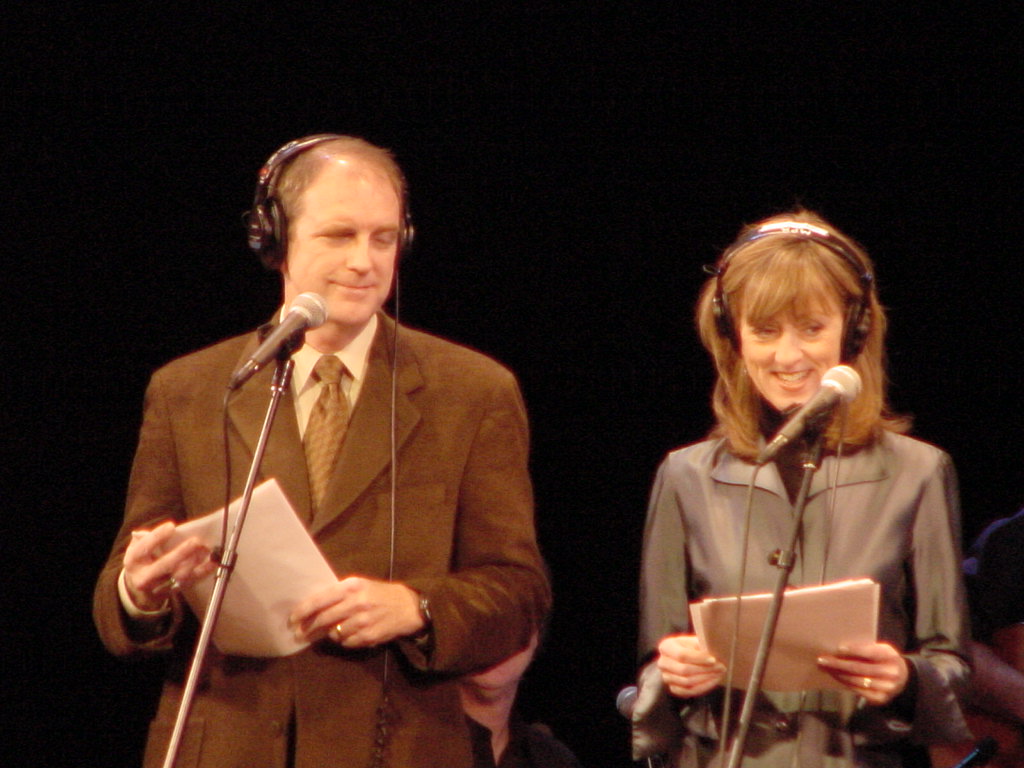

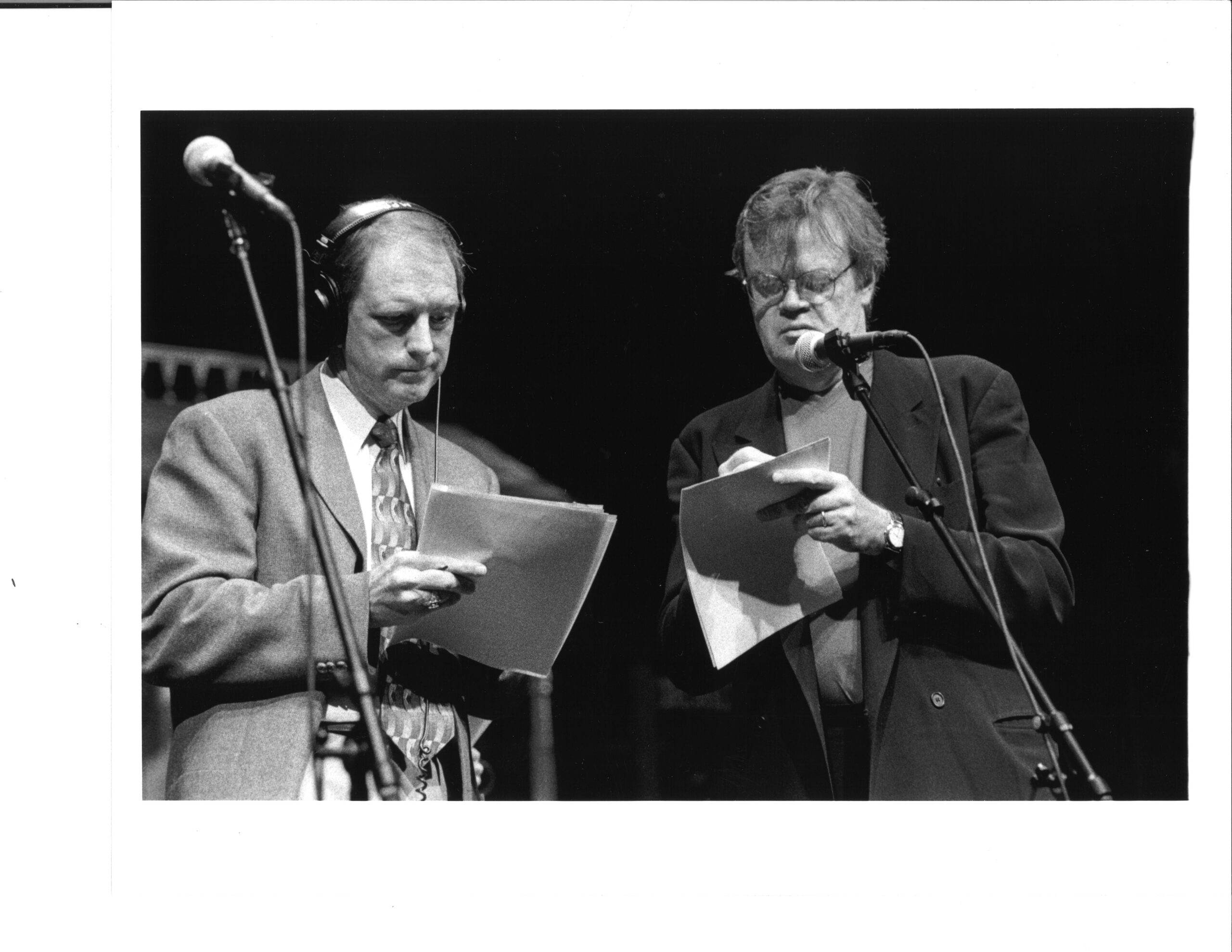

TIM RUSSELL, ACTOR

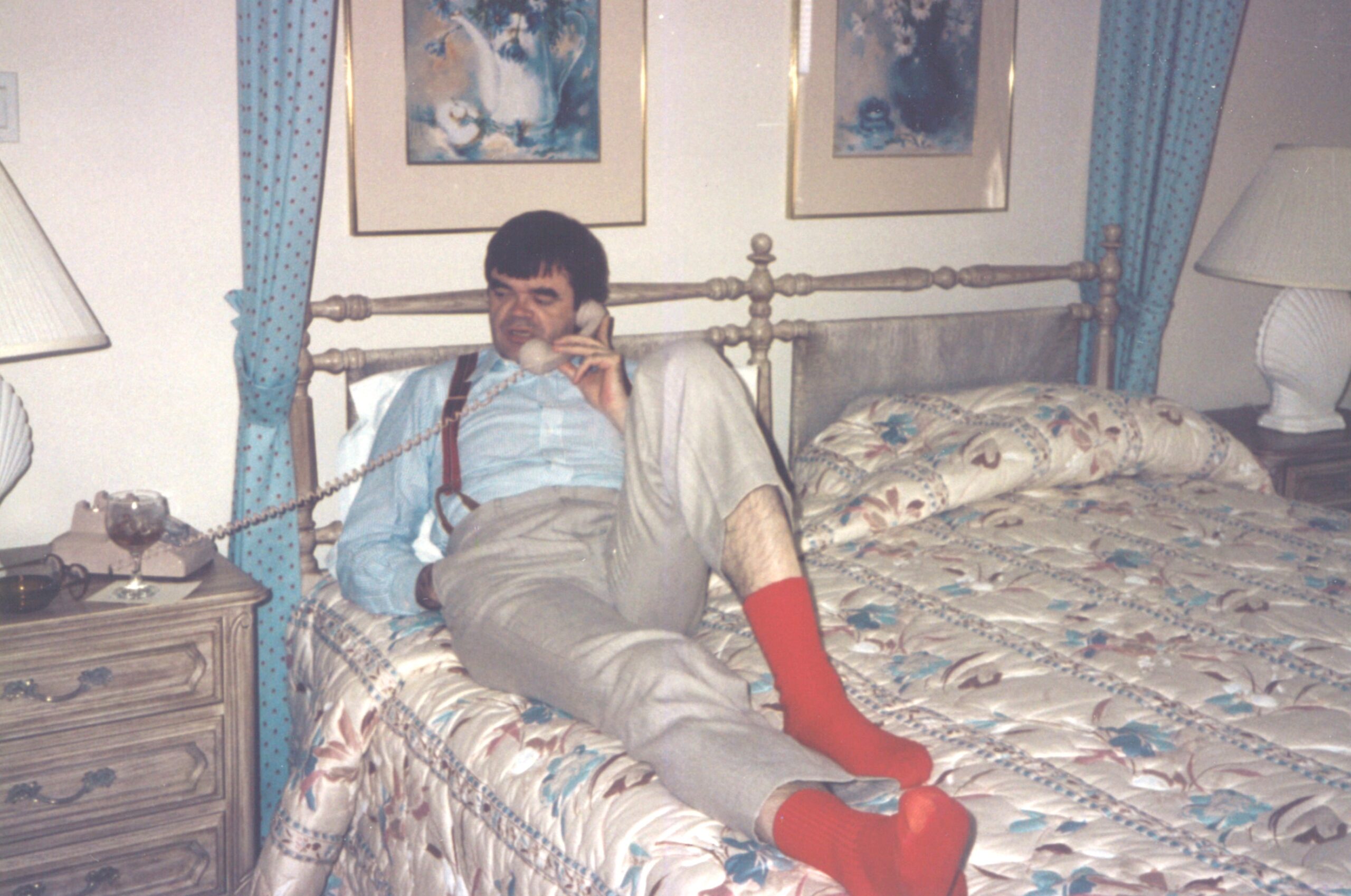

Garrison invited me to be on the show in May of 1994. My first show was in Portland, Oregon. I remember passing him at the door of the hotel on the day before the show, he said, “I’m going to buy some reds socks; I need to write something for you.” He wrote a script about “The Plaid Pants Warehouse” that featured my President Reagan impression, and we were off and running. Needless to say, I enjoyed doing the recurring characters: Dusty in “Lives of the Cowboys,” a chance to dig up a voice from the TV Western serials of my youth; Jim for The Catchup Advisory Board, which started out as a parody of the TV spots of ad guru Hal Riney, the voice of President Reagan’s “Morning in America” spots.

I had great fun doing the panoply of “Famous Celebrities” ruminating on the importance of various holiday’s or topical events, the voices of current and past politicians and presidents (the Washington Post noted that my “John McCain” was dead on; I told them his voice was a strange combination of Carol Channing and Liberace). There were also the many “Bob and Ray” nods as Garrison interviewed characters like my version of Paul Bunyan or F. Scott Fitzgerald. He challenged me with various dialects: the script might say (Italian) and I would have to create Italian gibberish and so on.

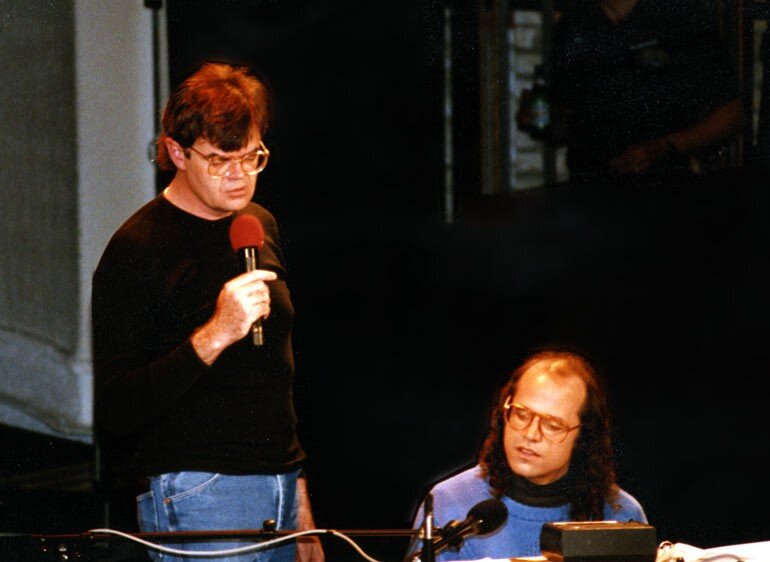

None of this would have been as fun without Garrison’s great script; his scripts made it easy to envision the voices needed and most of the time he didn’t tinker with whatever choice the actors would make. And if we were off the mark, he would guide us to a better choice. Garrison is a writing machine, it’s all about the rewrites, right up to showtime and sometimes during the show itself. There’s a picture of Garrison reaching around my shoulders — as I was reading a script on the air — and editing the script midstream. Most importantly, I enjoyed working with a great cast: Sue Scott, Fred Newman, and the late, great Tom Keith. Plus, the one-of-a-kind staff and technical crew that made every weekend a joy. The musicians were always world class, led by Rich Dworsky who was a valuable part of every script with his amazing, inventive, underscoring. The scripts would jump to life, thanks to Rich.

Then there was the opportunity to travel.

New York City: Taking the walk though Times Square to the legendary Town Hall on W. 43rd St. in NYC. Sharing a stage once trod by the greats in jazz, opera, folk, and spoken word. Downstairs — bathroom challenged, but full of camaraderie, Klezmer musicians and Broadway stars sharing curtained cubbyholes.

The energy of the great outdoor spring and summer venues.

Miami, where a bunch of deceased “Famous Celebrities,” like Jimmy Stewart and John Wayne, welcomed the recently passed Mr. Rogers to heaven. GK: “I’m sorry I wasn’t kinder to you Mr. Rogers.” Mr. Rogers: “That’s okay. I’ve talked to the Man upstairs and guess what.” GK: “What?” Mr. Rogers: “You’re not going to be my neighbor.”

Tanglewood, in the unparalleled beauty of the Berkshires. Quick jaunts to the Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, where his Four Freedoms paintings can bring a grown man to tears. Joined onstage with the likes of James Tylor, Meryl Streep, Sara Bareilles, and great classical musicians like Emanuel Ax. Major thunderstorms driving the lawn attendees under the great roof for epic marathon post-show sing-alongs, with everything from hymns and the great patriotic anthems, to the Beatles and Neil Diamond’s “Sweet Caroline.”

Wolf Trap National Park in Virginia, where the lawn crowds howl with enthusiasm at the mere mention of wolves. My imitation of Al Gore saying President George Bush’s policies creating a “giant sucking sound” sounded like something entirely different, drawing a light gasp from the crowd and some serious pearl clutching from the NPR listeners. “Did I hear word Sucking or something else?” Majority Leader Harry Reid was sitting on stage, and he evidently heard the “something else” and he loved it!

Ravinia, in the Northern Chicago suburbs, where one can visit a great botanic garden and drive up and down Sheridan Avenue wondering how so many people could make so much money. One year, we shared the stage with the howl of the 17-year cicada infestation. It’s where our beloved stage manager, the late Albert Webster, tracked impending storms on his computer.

The Hollywood Bowl, where guest Martin Sheen, The West Wing’s President Jed Bartlet got presidential advice from my Reagan, George W., Clinton, etc.

The Greek Theatre in Los Angeles, where the cool June nights were highlighted by the dramatic lighting of the amphitheater’s crown of vegetation, bringing out the best in a performer.

The Starlight Theatre in Kansas City, where one can sense that 105 degrees is not optimal for performing — but nonetheless Calvin Trillin and Kelley Hunt persisted.

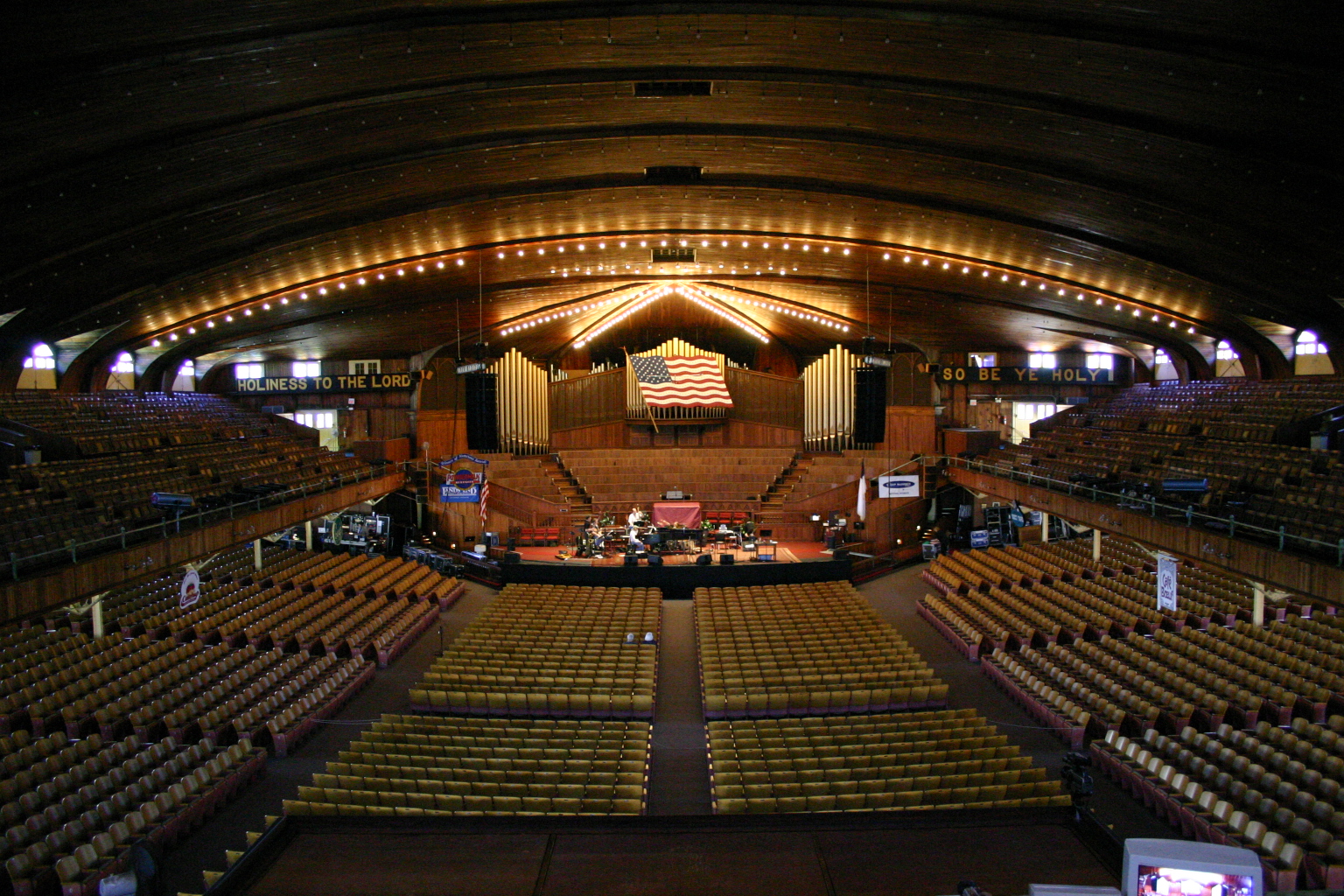

Nashville, the home of the Ryman Auditorium, where we enjoyed the likes of Emmylou Harris, Mark Knopfler, and Brad Paisley, sitting in with the band and, one time, bringing us a moment with Little Jimmy Dickens.

The Odd Spaces:

Canceled flights, a 13-hour rental car drive, nighttime in a snowstorm, to Bismarck, ND.

Sue Scott, Tom Keith, and Stevie Beck taking an 8-hour rental car drive from Denver, over the mountains at night, to Durango, CO.

Staying in the dorm at Interlochen Music Academy in Michigan — camp for grown-ups.

Lanesboro, Minnesota: a stormy Rhubarb Festival on-air show on a baseball diamond, where the weather knocked the satellite off the air, but Garrison soldiered on walking the muddy fields, microphone in hand joining the drenched crowd in song. Memorialized on film for the PBS American Masters documentary by Peter Rosen, The Man on the Radio in the Red Shoes.

The Minnesota Dance Hall Shows, where attendees are comfortable enough to chat you up while the show is on. So, where’s the men’s room then?

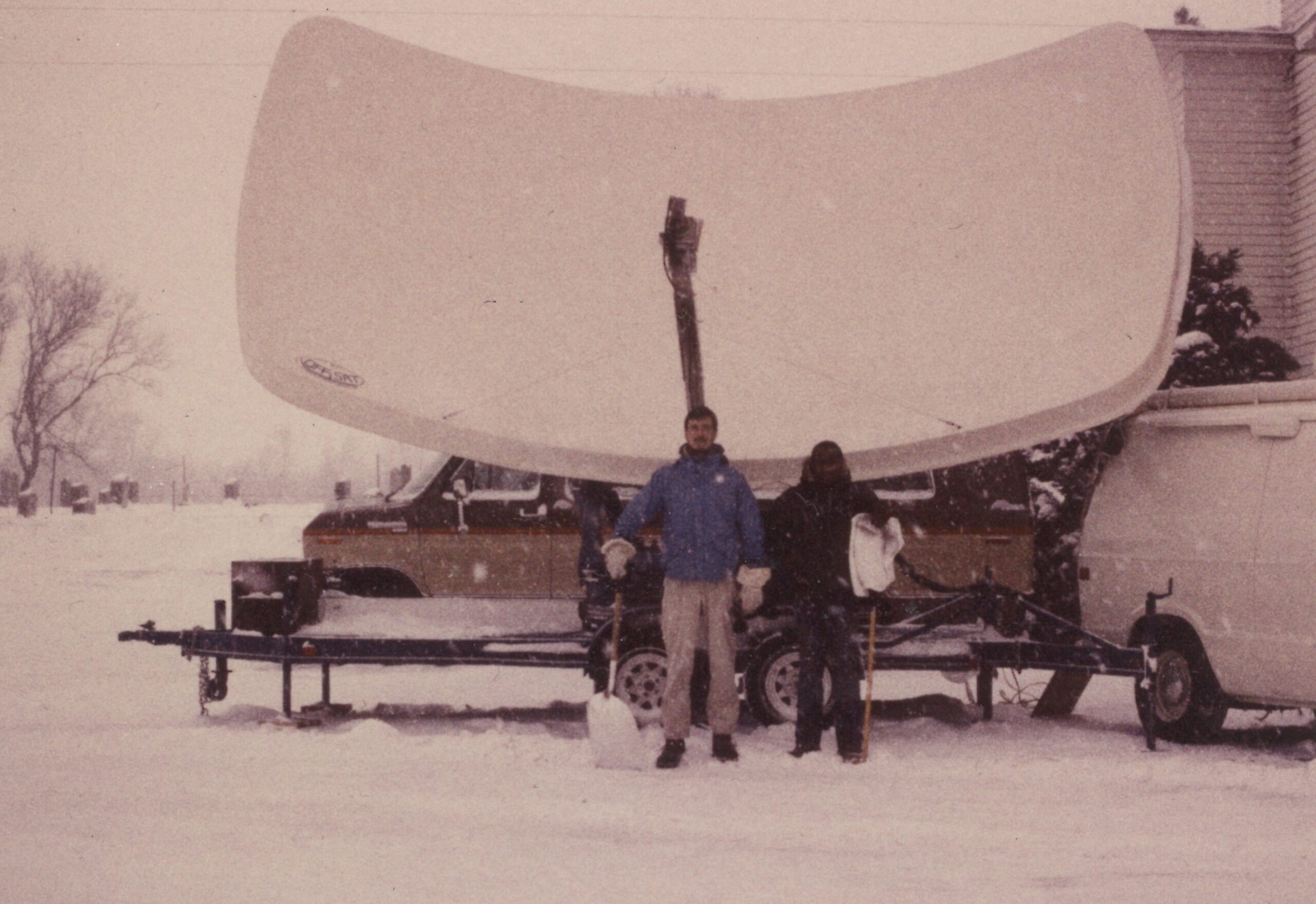

Yellowstone’s Old Faithful Lodge, wondering if this is the day that Old Faithful gives up the ghost. The Lodge Recreation center, good for basketball and bison, where a bull, rolling in the dust, threatened the broadcast satellite dish.

Flagstaff. A chance for a pre-show bucket list visit to the South Rim of the Grand Canyon, seeing a California Condor, with numbered tag, on a ledge below

New Orleans, LA. The rickety but famous St. Charles Streetcar takes you to within a few blocks of the WW2 museum, discovering the importance of a man named Higgins, the creator of the Higgins Boat, the heroic landing vehicle responsible for making D-Day a success. Trying to master the Cajun parlance for a script the morning of the show by listening to local talk radio.

Reykjavik. Learning to pronounce Eyjafjallajökull, the active volcano, almost as hard as Piscawaddaquadymogon (a word Garrison would throw in a script for some big shot visiting actor to be tortured trying to pronounce). The first screening of Robert Altman’s film A Prairie Home Companion, with Icelandic subtitles where “you can’t put the horse before Descartes” was subtitled “you can’t put a horse before Plato.” John C. Reilly was on the show from Iceland and loved jamming with the musicians in the wee hours.

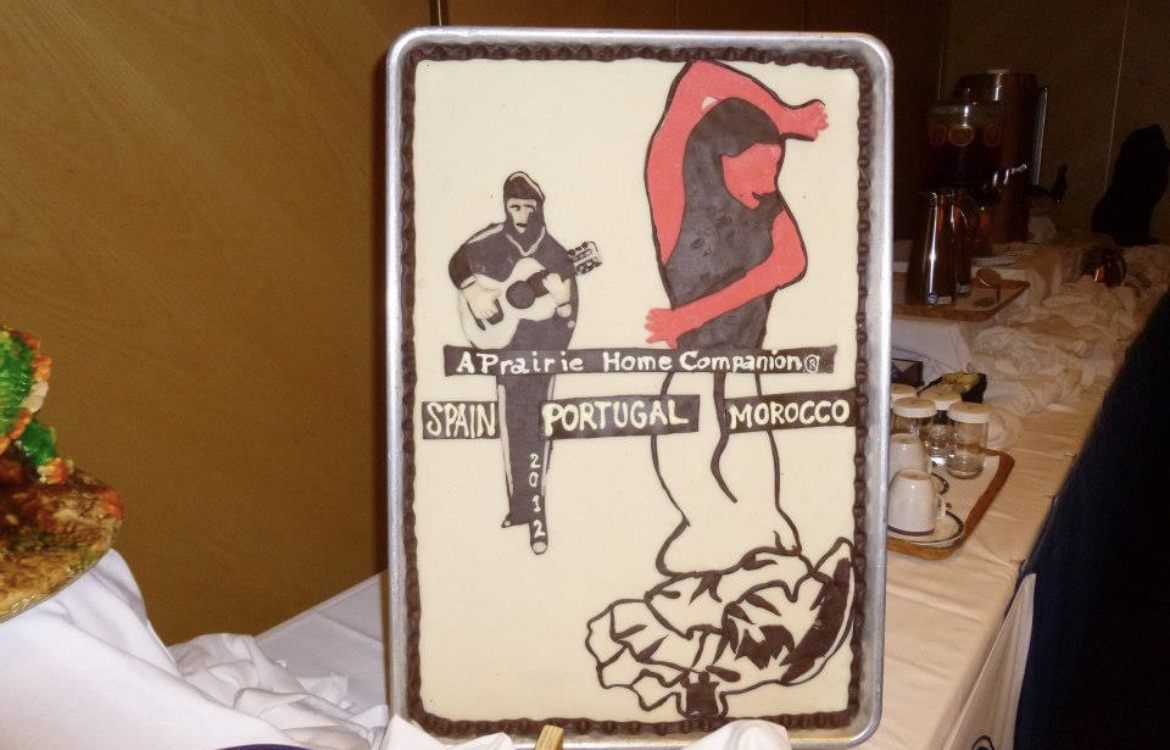

The Cruises. Garrison chartered Holland American Ships some 11 times for a cruise experience that brought talent and fans together for a chance to see the world. We did many APHC-like shows in the big showroom, and our guest musicians, singers, and poets would take over the smaller venues. Sue Scott and I would spend a couple of months putting together our own shows for the Showroom. Fine-tuning one of those shows would remind us of the skill Garrison had in putting together a 2-hour show each week for a national audience, an incredible feat.

The Summer Rhubarb Tour. The first of many non-radio APHC tours, one-nighters, covering the country. Sue Scott, Fred Newman, and I were on some of the first of these tours and it was deluxe: jetting to a city in a private plane (Pearl Jam’s touring plane), doing a show then flying to the next city, a stay in a hotel for the day, then doing the next show, then rinse and repeat. Later Garrison took just Fred, the musicians, and a guest singer like Suzy Bogguss or Sara Watkins for a couple of weeks on a magical mystery bus tour with a different theme each summer — two buses, lots of adventures.

JENNIFER HOWE, APHC OFFICE MANAGER AND PERSONAL ASSISTANT TO GARRISON

I joined A Prairie Home Companion in 1984 and immediately began to tour with the show. The entire experience was new to me, and I fell in love with the vast array of theaters, their history, “phantoms,” and construction. One theater had numerous balconies, the top few rows at an almost vertical angle, narrow stairs and only a knee-high guard rail. The pitch was such that you were sure you were going to fall over the railing. It was so high from the main floor that a person could hardly see the actors on the stage. Some venues were gothic, others Pepto Bismol pink, ultra-modern or quaint — each one more interesting than the one before. My favorite was a theater that resembled a Sultan’s tent.

Today the technicians use a computer; however, the original backstage control panel resembled the wall of a battleship. Large hand cranks, knobs, buttons, dials, and steering wheels to move the screens, curtains, and lights. During rehearsal, I asked one of the techs to explain the controls and he informed me that the ceiling could be illuminated to produce a sunset, stars, and sunrise. I showed Garrison and he talked the procedure through on the radio. The ceiling had not been lit for some time and everyone was thrilled to see it. There were ooohs and aaahs from the audience just like you hear during the Fourth of July fireworks.

George Lunn, Chet Atkin’s Road Manager, was on the my few road shows and took me under his wing — a great mentor and friend. Chet and my husband, Bob, became friends over the years. One day Chet called and invited us down to Nashville, all expenses paid, for his famous Celebrity Golf Tournament and party. Bob golfed in Chet’s foursome — an experience that neither of us would ever forget.

My first trip with Garrison was about three weeks after my start date. The cast and crew had already departed, and Garrison and I were taking a later flight. Departing the airport, I saw a long white stretch limo waiting at the end of the sidewalk. The driver was holding the door. I climbed in, followed by Garrison and to my amazement, across from us were Chet Atkins and Johnny Gimble. All I could do was think to myself — Jennifer Mathwig Howe, Cumberland, WI, population 1897, sitting in a stretch limo with Garrison Keillor, Chet Atkins, and Johnny Gimble. Needless to say, I pinched myself a dozen times!! And the adventure of a lifetime began.

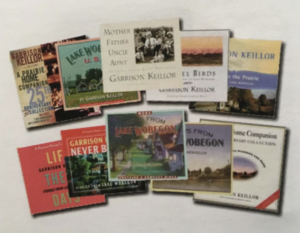

Fan letters were abundant — everything from advice, thank-you notes, pictures of family gatherings, gifts. A few that stand out were from a chaplain, an inmate, and a college English class. The chaplain wrote from a military base in Europe. He had taken one of Garrison’s tapes with him and had played it so many times with the troops that it was worn out. I boxed up one of each of Garrison’s tapes and books and forwarded the package to the chaplain. We were happy to hear that it arrived in time for Christmas. The chaplain’s thank-you read that a number of the boys never received mail from home, so this was a very special gift. Students dissecting one of Garrison’s stories in an English class found a grammatical error. As a class project, they composed a letter spelling out the error to Garrison, each one signing the letter. Garrison asked me to send another gift box of his books and tapes and off it went with a letter of acknowledgement and thank you from Garrison. An inmate, in for life, found solace in Garrison’s work and asked if we could send tapes and enlist our services to get the show on the local airwaves. We were unable to accomplish the latter, but we boxed up a season’s worth of tapes, in addition to some of Garrison’s products and sent them off. Because the show tapes were not shrink wrapped, the concern of the prison staff was that they could contain secret messages to the inmates, escape routes and such, so it was a strict prison policy to return this type of material to the sender.

One memorable package came to our office after Garrison had mentioned in a monologue how he missed the sweet aroma of cow manure. Sure enough, along came a two-pound coffee can filled to the brim!

One book autograph request was from a man in Australia. Garrison turned the book upside down and inscribed, “To _____, in the land down under,” Classic and brilliant as always.

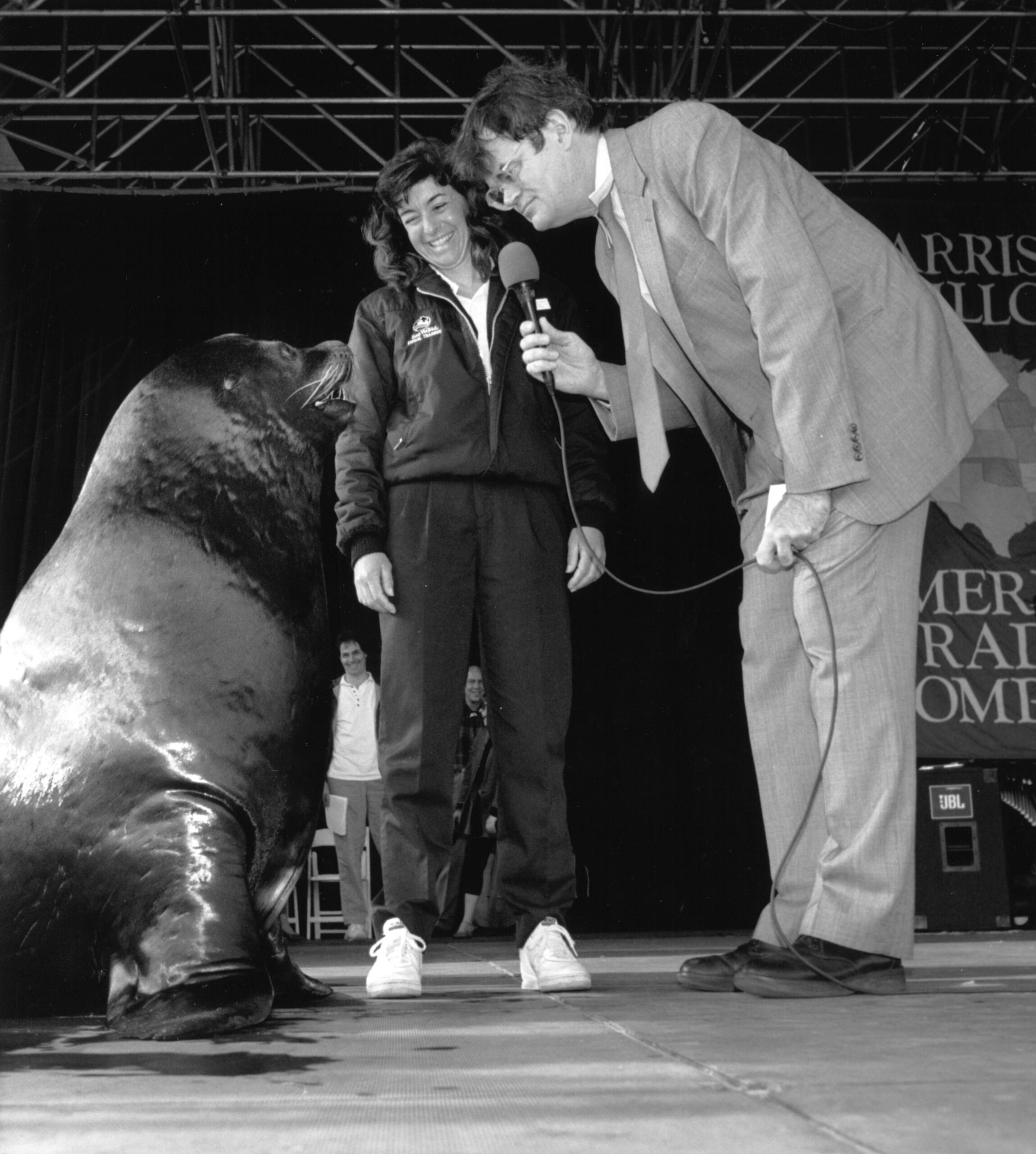

One of the many benefits of working with Garrison and APHC was the opportunity to meet his vast array of guests and to hear such a wonderful variety of music. And as exciting and humbling as it was to meet some of the all-time legends, I have to admit one of my favorite guests was “Murray,” the 800-pound sea lion from California’s SeaWorld. There is an incredible photograph of Garrison leaning over addressing Murray. When Garrison put his microphone in front of Murray, hoping for an audience laugh, Murray surprised us by talking back. Much to Garrison’s (and our) amusement, he barked back an answer to every one of Garrison’s questions. Garrison’s facial expressions were priceless. They went back and forth for several minutes, and it brought the house down! When Murray had to depart for his next “performance” he took a bow, waved his flipper at the audience and waddled off to his travel cart down a special plank we had built for him. He was doused with water to keep his skin from drying out, and off he went, barking at us all the way out. What a variety show! It was the only time I saw Garrison upstaged.

Garrison’s willingness to accept outside speaking engagements — in addition to writing, producing, and hosting a weekly show — was remarkable. In most cases, a request for Garrison to “stop by and greet volunteers of a hospital or church during their lunch break” would turn into a full-blown two-hour benefit performance, in a theater that held 2,000 people. Garrison would insist that all proceeds go to the charity the volunteers were working for. It is amazing how Garrison gives of his time and talents.

The final Saint Paul APHC broadcast in 1987 was a day none of us looked forward to. The performance was flawless, filled with emotion for all who performed, worked, or listened. My husband was waiting in our Jeep in the alley behind the stage door to whisk Garrison away to a private farewell function with family and friends. Garrison’s loon calls, as lonely and heartbreaking as they sounded, were also a ray of hope to all of us that Garrison and A Prairie Home Companion would someday return. None of us could begin to imagine Garrison’s feelings. We each experienced our own mourning and sense of great loss. But for the creator and host — who had spent so many years onstage — it must have been a very sad day indeed. It was then wonderful to know our feelings about the loon calls were correct: Garrison returned, and the show continued for another thirty years. Congratulations on your 50th Anniversary!

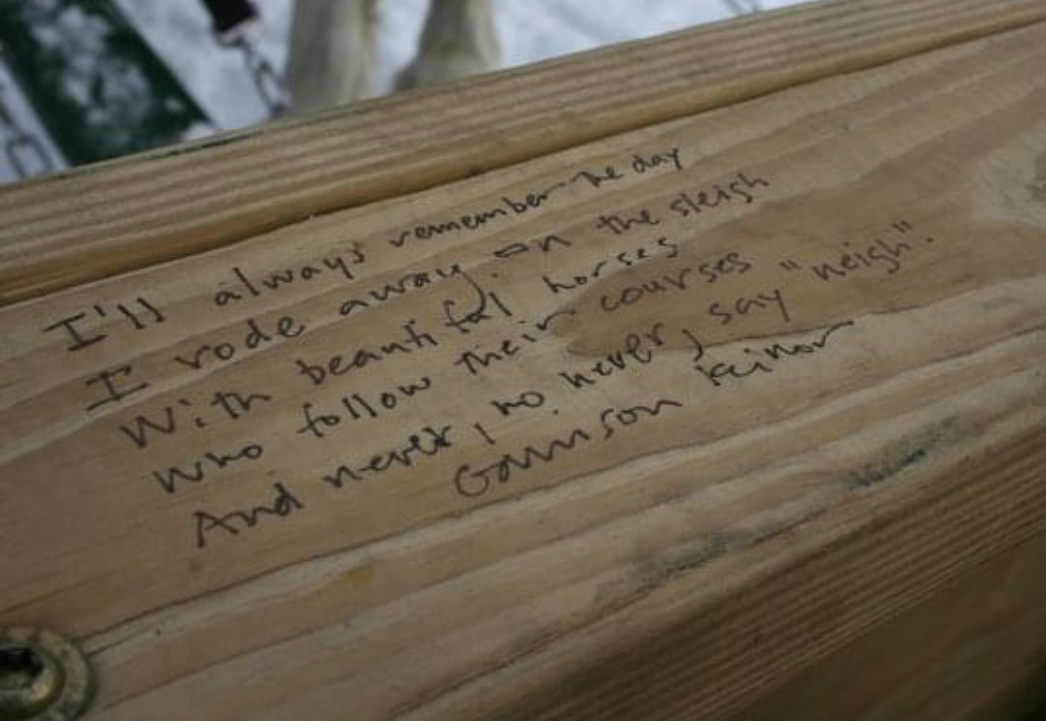

POP WAGNER, SINGER, SONGWRITER, PERFORMER

Early years

The first time I played on the show was in 1974 or 1975. It was at the small theater space in the Park Square Court Building (where the radio station was also located at that time). I remember the feeling of excitement over its being a LIVE broadcast although the in-house audience was relatively small. In the early years, I was a frequent guest and played on shows at the Science Museum, the Sculpture Garden, and the World Theater. I remember volunteering with many others as we cleaned up the old World Theater, getting it ready for the public. In those early years, the entire cast and crew would often go out to dinner together after the show — a great feeling of camaraderie! Once when the show was being broadcast from the Sculpture Garden, it started to rain. The broadcast was briefly switched back to the station and everyone (cast, crew, and audience) picked up a mic stand or other piece of equipment and carried it across the street to the World Theater. We were back on the air within 5 or 10 minutes as I recall!

The show goes national

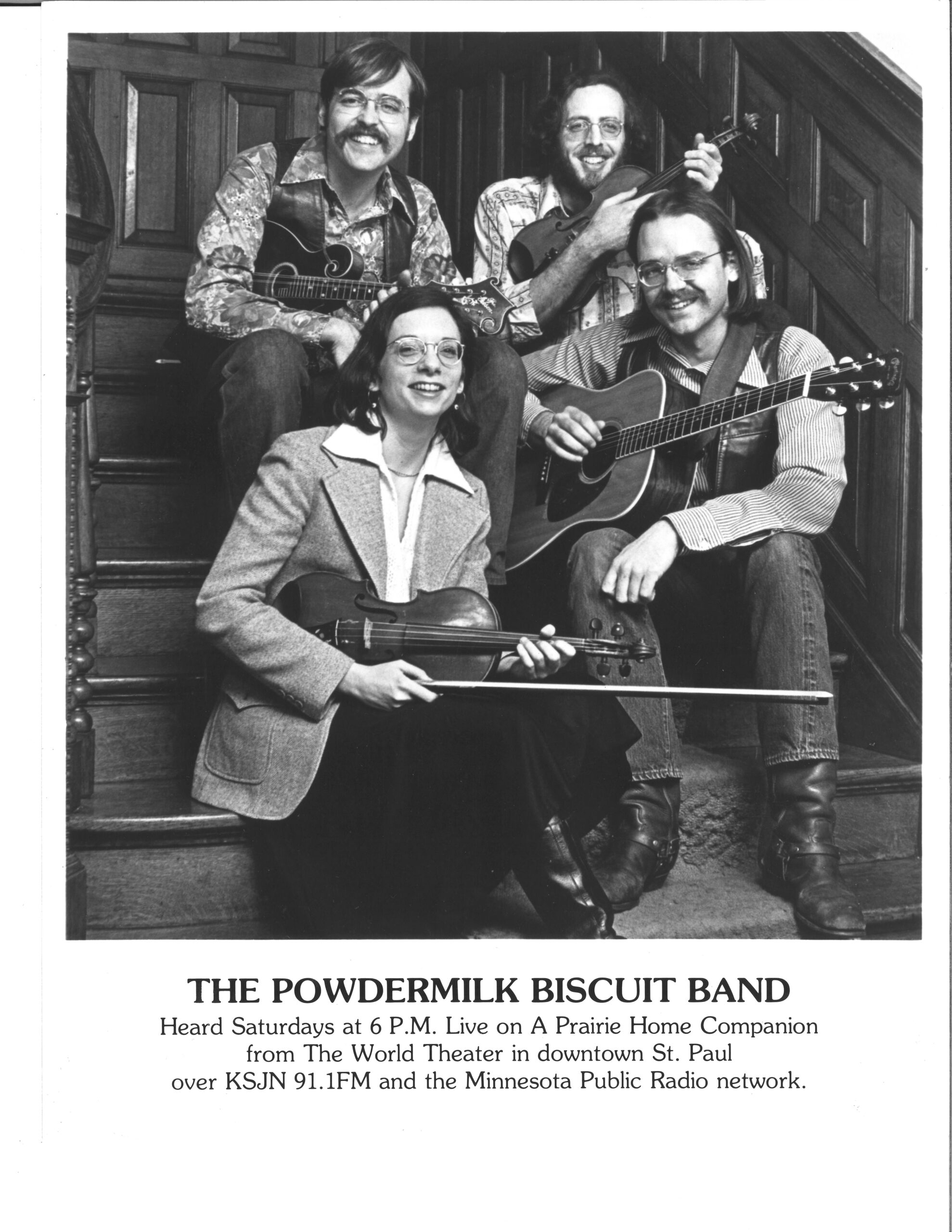

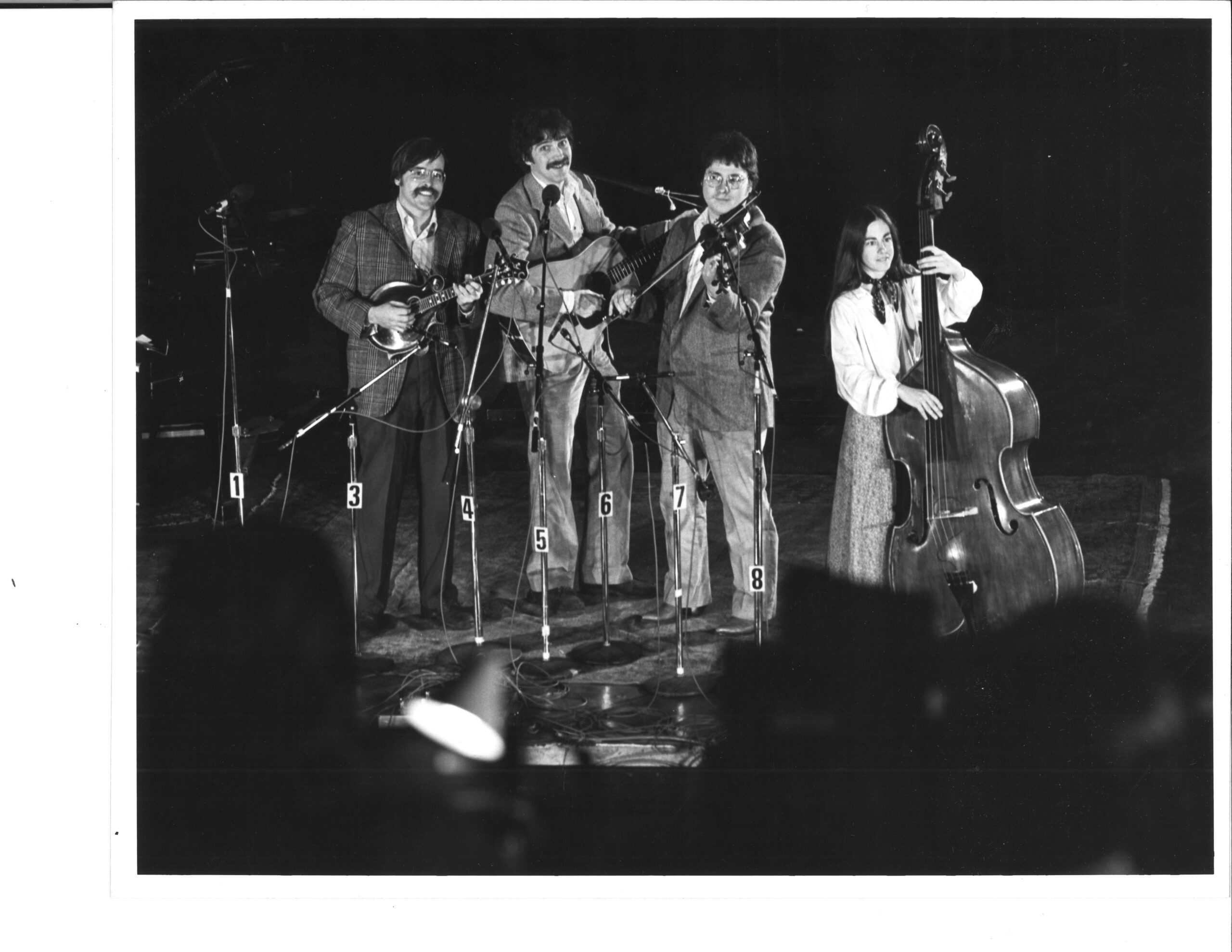

I had the honor (along with the Butch Thompson Trio, the Powdermilk Biscuit Band, and others) of being on the first national broadcast at the NPR convention in Kansas City. I believe this was being considered as a “trial run” of sorts. Later, when the kickoff show for the regularly scheduled national broadcasts was held at Northrop Auditorium, I was the first solo to perform after the introduction — the excitement, almost electric, was palpable in the air! And a full house sang along with me as I played Libba Cotten’s “Shake Sugaree.”

The movie

During my first day on the movie [Robert Altman’s A Prairie Home Companion] set (as a musician extra), I was in a scene with Lily Tomlin, Meryl Streep, and Lindsey Lohan. I was instructed to pass by them as they entered the green room area. The cameras rolled and I walked. Then as I was passing by, Meryl said, “Good morning, Pop!” and I responded with “Howdy, ma’am!” — at which point someone hollered, “CUT!” Well, then I was taken aside and told NOT to say a word since it would have put me in a much higher pay grade. I like to think that somewhere on a cutting room floor there is footage of me trading lines with Meryl Streep!

PAT DONOHUE, GUITARIST

One segment on the show I will always remember was in 1994 when we did a Prairie Home show for the grand reopening of the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville. It was a star-studded show. One bit was the “Everly Brothers Singing Contest,” in which there were three “teams” of duo singers. We (the Guy’s All-Star Shoe Band) played “Dream” (by the Everlys) and Kate MacKenzie and G.K. sang the first verse and did great. Vince Gill and Mary Chapin Carpenter sang the second verse and the crowd went wild. Then, the actual Everly Bros. (who were also on the show) came in on the middle part — “I can make you mine, taste your lips of wine, anytime night or day” — with their iconic sound fully on display and at that point the crowd went totally insane with happiness, me included.

Another thing I will always remember happened after a Dec. 21 APHC show at The Town Hall in NYC. It had started snowing … hard! We were supposed to fly back home the next day as usual, but I chose to get in the truck with our beloved driver Russ Ringsak and ride back to Minnesota with him, since I didn’t want to get snowed in. It was coming down like crazy and I had my doubts as to whether or not Russ could drive us out of Manhattan in such a storm in that big red APHC semi. Well, sir, I saw a masterful exhibition of truck driving that not only got us out of New York but also safely home in about a day and a half. Those who stayed were snowed in for several days. I hope they all made it home for Christmas. I know I did, thanks to Russ. I had a great time on the ride too, listening to blues and playing my guitar in the passenger seat. God bless Russ.

SUZANNE WEIL, ARTS ADMINISTRATOR AND PRODUCER

I ran a one-person Performing Arts program at Walker Art Center in Minneapolis beginning in the late ’60s. We were a discerning, I might say a bit hard to please, small staff — a relentlessly sophisticated young bunch. If there had been a water cooler, we would’ve all be around it each morning talking about the Prairie Home Companion.

That guy in the tiny booth in a tiny town? I have no idea how we got there; I’m certain that there was no such thing as a publicist, given the time and the resources, laughable. The juxtaposition of that little town somehow brilliantly funny and always respected, perhaps that is the crux of it all. There was music you wanted to hear but didn’t know it. If “Help Me, Rhonda” didn’t set you up for the day, forget it …

I’ve complained about the loss of Jack’s Auto Repair and Raoul’s Warm Car Service (a particular favorite). I don’t remember who survived those early programs — was Pastor Liz there? I don’t think so.

He made them funny but never talked down to them. The listener didn’t have to feel guilty laughing at them — ever.

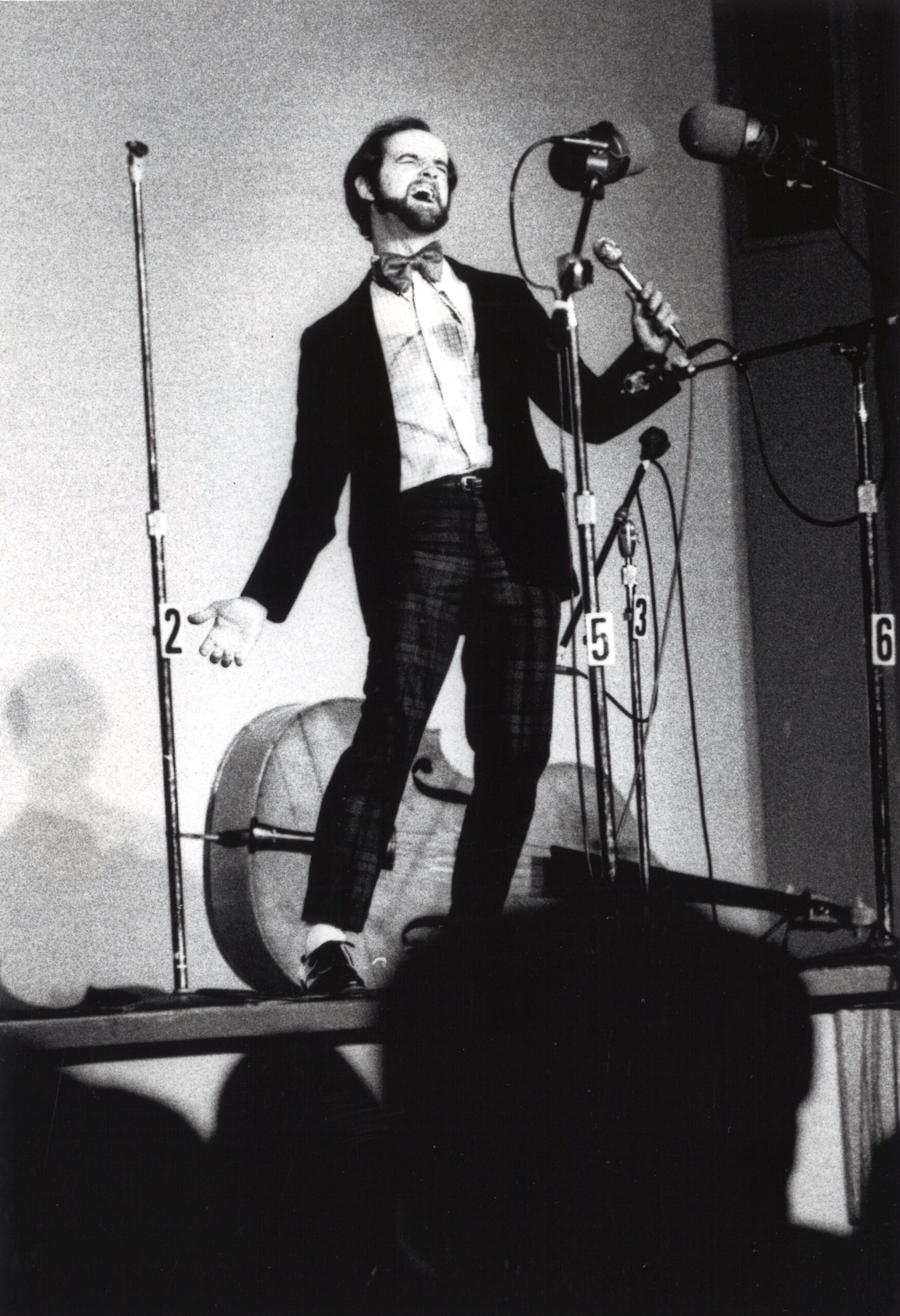

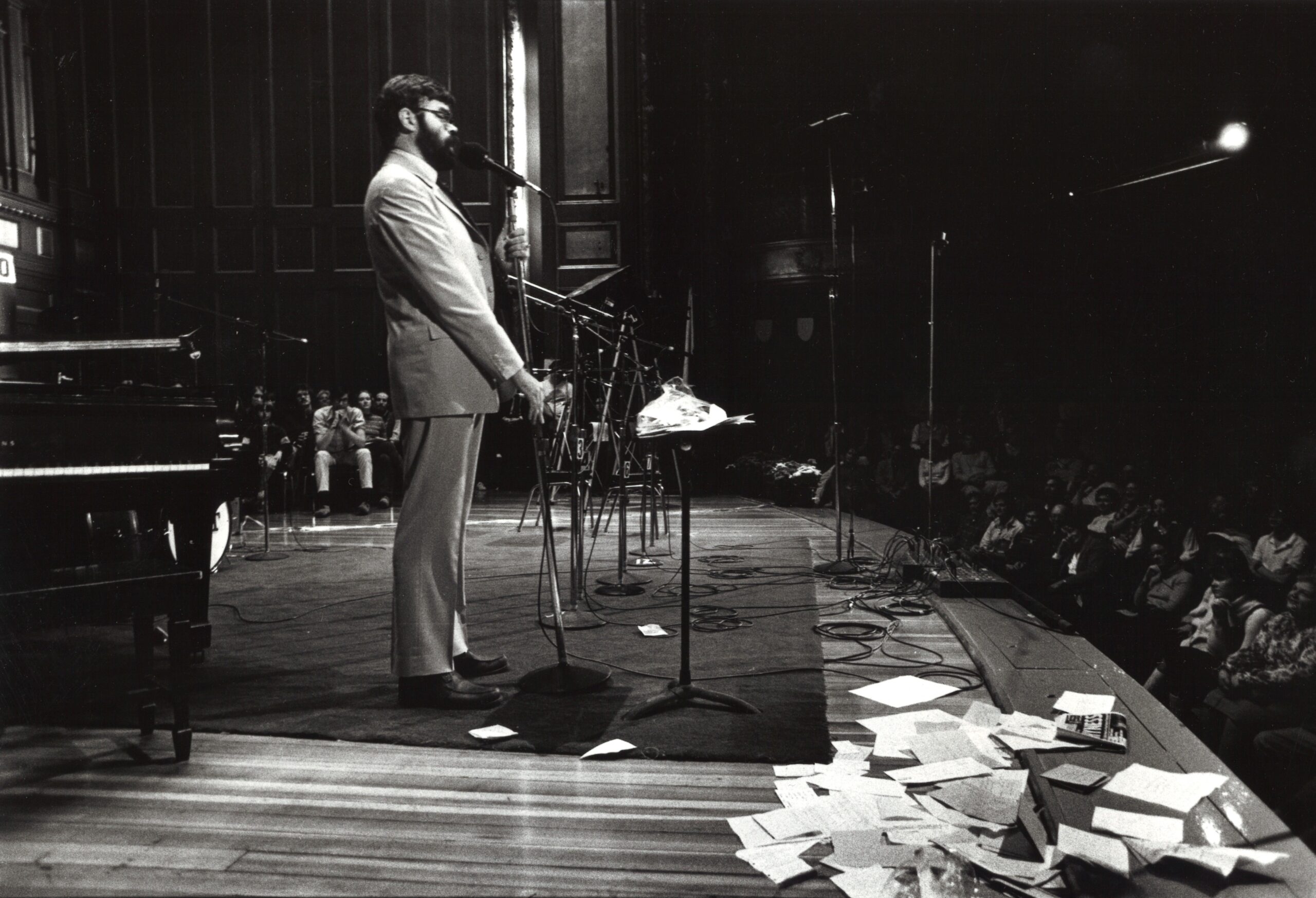

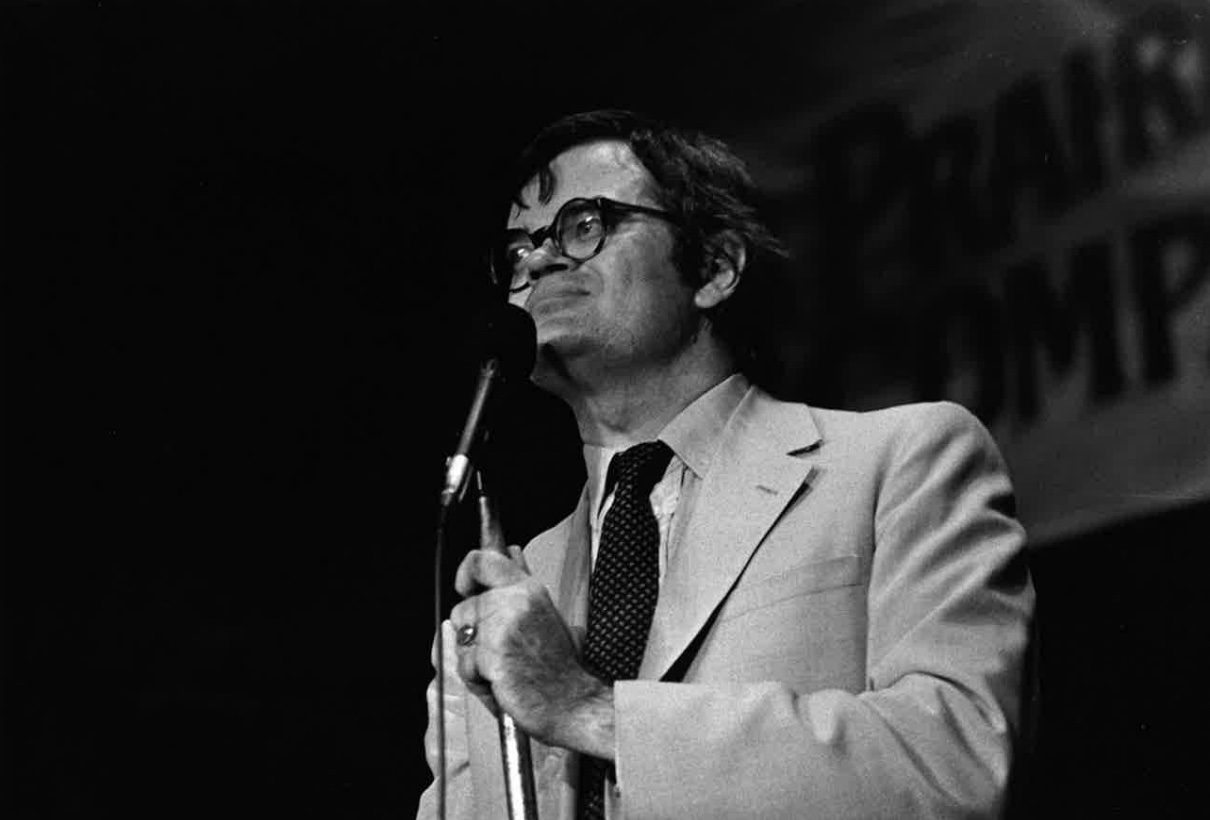

I had gotten to know Garrison when I presented a poetry reading of Garrison and the late Peter Schjeldahl (Art Critic at The New Yorker for many years, a Minnesotan) at the Planetarium at the Public Library. GK’s Richard Nixon poems stand out. I suggested a live program at the Walker Art Center Auditorium (“listeners would like to see what you look like”). We presented A PRAIRE HOME ENTERTAINMENT with others at the Auditorium at Walker Art Center. That seemed to be the beginning of something, I’m not sure what exactly.

I think those of us who found him then have a right to be a bit smug — I am.

MARCIA PANKAKE, PERFORMER (WITH HUSBAND JON PANKAKE), EDITOR OF A PRAIRIE HOME COMPANION COMMONPLACE BOOK AND A PRAIRIE HOME COMPANION FOLK SONG BOOK

The Masked Folk Singer

It was Garrison’s idea that traditional music scholar and musician Jon Pankake appear on A Prairie Home Companion as “The Masked Folk Singer.” Wearing a red mask, Jon would take the stage and sing a song. For one such appearance, Jon had been instructed to enter the theater during the broadcast through the loading dock door — behind the curtain at the back of the stage. Finding that door locked, Jon and I went through the theater’s main door, where we were met by some resistance from a staff and crew unaware of the plan. Bill Kling, president and CEO of Minnesota Public Radio, thought the Masked Folksinger bit was awful, especially on shows with the likes of Chet Atkins or The Modern Jazz Quartet.

“Just say goodnight …”

Like many listeners, we can remember where we were when we heard a certain show. We were picking raspberries in the backyard, and at 5 o’clock set things aside, got our lawn chairs and sat down in the yard to listen. It was the show from Alaska in which the News from Lake Wobegon ran long. I was thinking. “Oh, maybe the show is going to be more than two hours today.” Later on, I heard that Garrison had dug himself into a convoluted monologue and it was stalwart stage manager Steve Koeln who — as the clock ticked down — kept going out on the stage to show GK signs: 5 MINUTES. Then, 2 MINUTES. And finally, JUST SAY GOODNIGHT!

The Prairie Home Attic Show

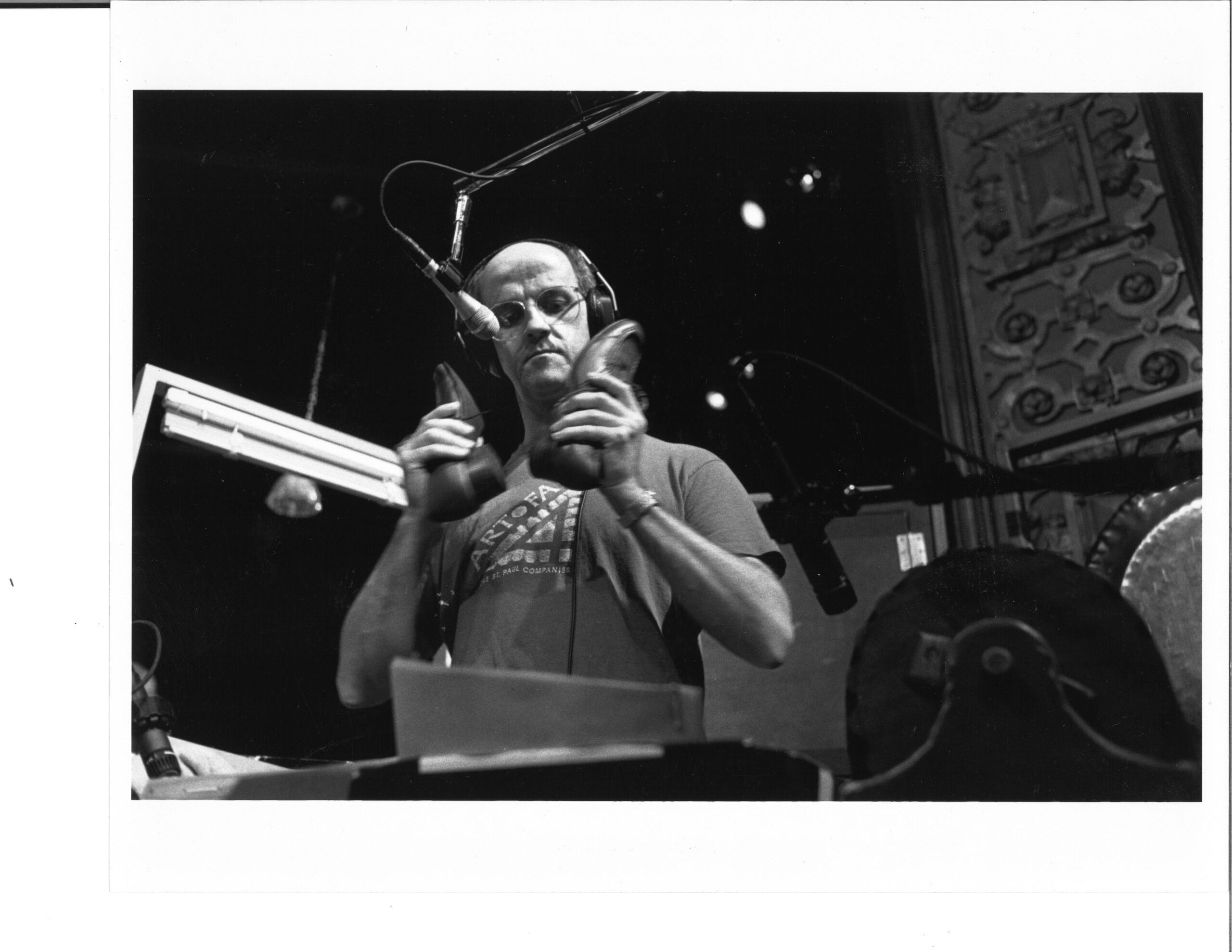

I think this was the first time Garrison ever took time off from the Saturday show, and he may have still been doing KSJN’s The Morning Show as well. But he asked us to put together a broadcast of recorded music (from “the attic”), and so we listened to a lot of things and played a few things for him and came up with a show. I sat with engineer (and sound-effects man) Tom Keith and we assembled the recorded pieces. We had Garrison on tape speaking something and we were going to connect that to something else, but he had breathed out rather than in — or in rather than out — just where the join was going to be. Tom worked on that one recorded breath for an inordinate amount of time before we got it cut just right.

The project was great fun because “the attic” included lots of recordings from the 1930s. GK had told us that we should contact the still-living people we could find to get permission to use their recordings — typical of his thoughtfulness. I wrote to the DeZurik Sisters, for example. Carolyn and Mary Jane DeZurik — who grew up in the tiny town of Royalton, Minnesota, and went on to appear regularly on Chicago’s National Barn Dance — were very excited that we wanted to use one of their records. Later on, one of the sisters wrote back, telling me that they had gathered the family together and listened to the show. They were tremendously thrilled to hear their old recording.

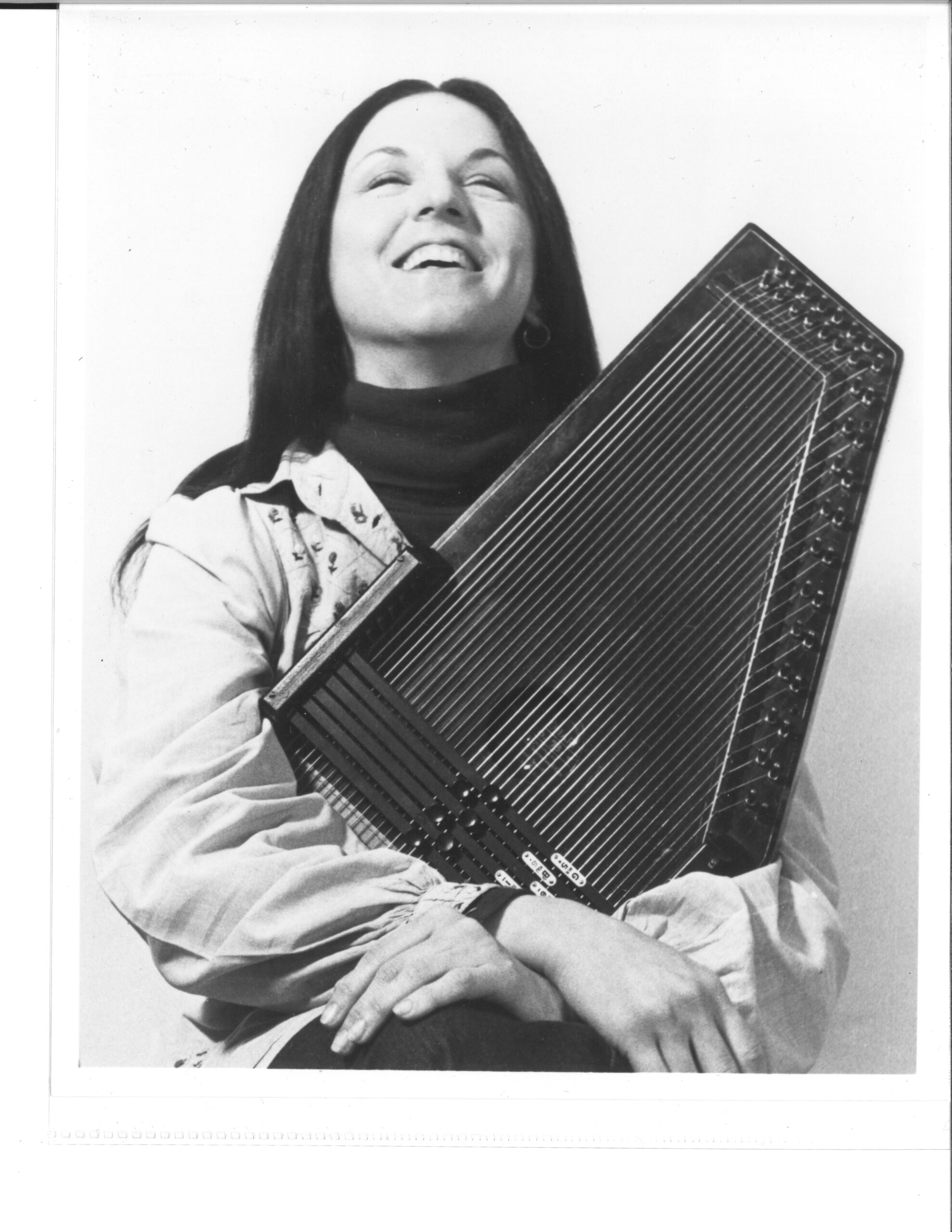

STEVIE BECK, PERFORMER, ASSOCIATE PRODUCER

At the Ryman

I remember when Garrison went down to Nashville in the spring of 1974 to see the final Grand Ole Opry show held in the Ryman Auditorium. For several months, he had been taking music lessons from me, and at our next session, he brought me a picture of the Carter Family, which I still have. He also returned with an idea for a live radio show: A Prairie Home Companion.

The Ryman had been home to the Grand Ole Opry since 1943, and thirty-one years’ worth of performers added up to a big chapter in the history of country music. For some of us who listened to WSM on Saturday nights, when Roy Acuff, Minnie Pearl, Ernest Tubb, and Loretta Lynn performed on that stage, the 1974 move to Opryland USA didn’t sit too well.

During the next couple of decades, only the occasional recording session or special event brought music back to the Ryman. The building, falling into disrepair, was open daily — 8:30 to 4:00 — to busloads of tourists who paid $2.50 for a chance to see a collection of memorabilia from the glory days.

Then in 1993, an $8.5 million renovation began, which would bring the “Mother Church of Country Music” back to life. Greg Pope at WPLN Nashville Public Radio and the Ryman Auditorium staff invited A Prairie Home Companion to kick off the grand opening celebration, And with APHC’s broadcast on June 4, 1994, live radio returned to the Ryman.

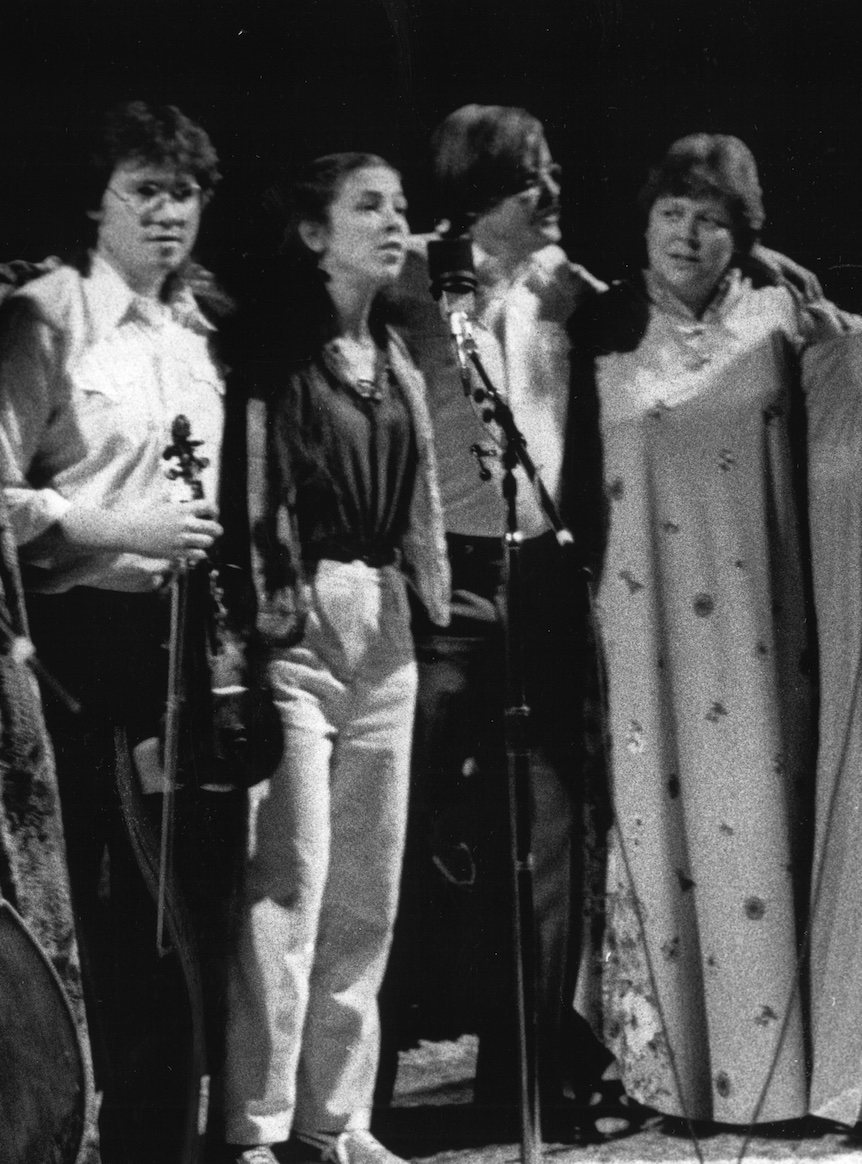

During that afternoon, PHC’s guest performers — including Chet Atkins, Vince Gill, Mary Chapin Carpenter, Kate MacKenzie, Robin and Linda Williams, Don and Phil Everly, and Mark O’Connor — wandered through the Ryman’s oak pews and recalled their own connections with the venue. Don Everly told me that back in the 1950s, he and Phil spent two solid years standing in the alley between the Ryman and Tootsie’s Orchid Lounge, hoping they’d be invited onto the Opry stage. And, he added, every time Chet Atkins came out the stage door, he’d introduce the Everlys to whomever he was with and comment on the boys’ talent. Chet himself remembered being a boy of ten when someone told him, “Keep on playing that fiddle, Chester, and someday you’ll be on the Grand Ole Opry.”

What stays lodged in my memory of that day is the thrill of standing on the stage where Maybelle Carter once sang with her daughters; where Roy Acuff did “The Wabash Cannonball” and balanced his bow on his nose; where Minnie Pearl’s piercing “Howdy! I’m just so proud to be here” carried all the way to the parking lot; and the likes of Red Foley, Kitty Wells, Uncle Dave Macon, Hank Williams, and Patsy Cline stepped up to the mic on Saturday nights.

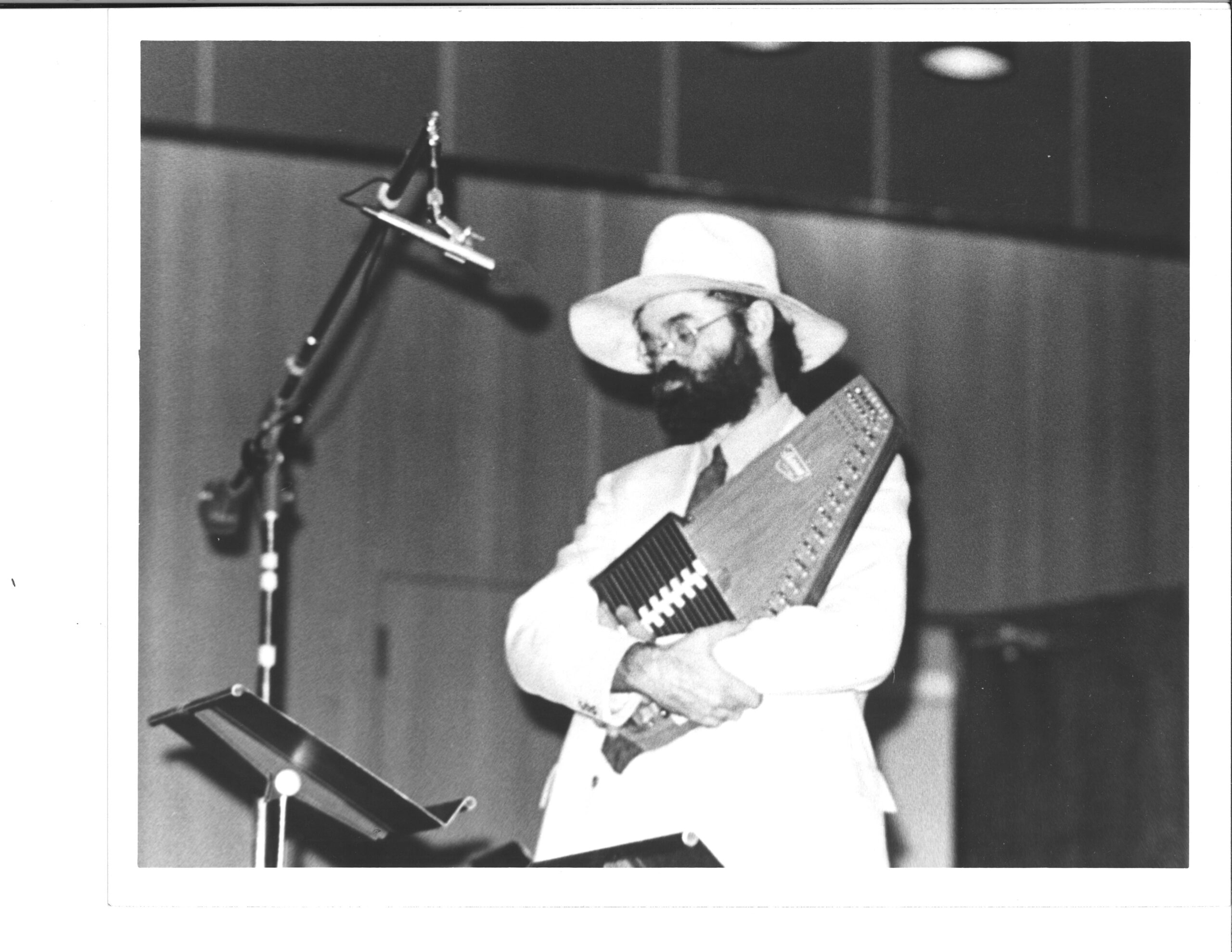

First appearance on A Prairie Home Companion

After Garrison received an Autoharp for Christmas in 1973, he began taking lessons from me early the following January. The lessons lasted only a few months, but that summer he called and invited me and my music partner, Bob Bovee, to play on his new radio program. Our first APHC appearance was October 19, 1974, the first time he dubbed me the Queen of the Autoharp. It was Prairie Home’s sixth show — and audience attendance was holding steady at about 12.

Early days

For the first few years, the music performers played the parts of characters in the scripts. I was once cast as Jessie James in an all-female version of the James Gang. On another show, I played a trucker named Little Queenie, hauling a load of bat guano in my eighteen-wheeler. Later, APHC stepped up its game and booked real actors — a marked improvement. All the while, Tom Keith provided the sound effects. He was a genius at his craft and made poetry of every footstep, faucet drip, helicopter flyover, car tire spinning on ice, even (wince) a cornea removal. After Tom’s death, sound-effects duties went to Fred Newman (the envy of any 14-year-old who ever put palm to armpit).

Associate Producer

I performed on A Prairie Home Companion five or six times a year until the show folded its tent (the first time) in 1987. And a couple of years after the program was resurrected (as American Radio Company of the Air before returning to the original title), I was offered the position of associate producer, in charge of booking talent.

During rehearsal on show days, the most frequent question I got from the guest performers — out of their element in our production style — was, “How do I know when to start?” I’d always tell them, “Just listen to Garrison when he introduces you and chats with you. He’ll say or do something that’ll seem as though he’s handed you a downbeat on a silver platter.” True.

In New York

Working on a Prairie Home Saturday broadcast in St. Paul could be challenging, but doing the show in New York flummoxed me. Everything felt like a struggle. Our ad hoc office at The Town Hall was on an upper floor, a space you got to by elevator — that is, if you could find the elevator operator. One December Saturday, shortly before airtime, I had completed some last-minute task in the office and then rang for the elevator.

The minutes — five, ten, twenty — ticked by. More ringing. No luck. I considered taking the stairs but thought the better of that idea when I peeked into the stairwell and found it so dark that I could barely make out the pigeon corpses that littered the steps. Rescue finally came after I made a (then) long-distance call to the tech director’s cell phone, and he got someone to track down the elevator guy.

In the words of our wonderful stage manager Steve Koeln, “If you need a piece of plywood in St. Paul, you zip over to Knox Lumber and get one; in New York, it takes three hours, two unions, and a trip to New Jersey.”

KEN LAZEBNIK, WRITER

My wife, Kate, and I moved to New York City in 1985, driving out from Minnesota in an old Chevy Nova my parents had bequeathed us. When I lived in St. Paul, I had listened to Garrison’s morning show, and then Prairie Home Companion, with star-struck admiration. (I graduated from Macalester College in 1976, unaware that one summer when I was preoccupied with doing summer theater productions there, PHC was broadcasting from the music hall at Macalester.) The brilliance of the writing — the uncanny combination of inspired absurdity of the sketches, balanced with the profoundly human storytelling of the monologues — created a magic I’d never heard before. But I had never met Garrison or connected with PHC in any way when I lived in Minnesota.

When Garrison returned from his Denmark hiatus, he wanted to launch a different show, one based in New York. It would be a two-hour variety show, like PHC, but without the Midwest as its touchstone. He hired Minnesota composer Randall Davidson as his initial producer of The American Radio Company of the Air, and he set up the office of The American Humor Institute in an old building on 14th Street. In one of life’s serendipitous turns, Randall and I were childhood friends; we’d both grown up as sons of professors who taught at Stephens College, in Columbia, Missouri. Randall contacted me and said Garrison was looking for a writer. He invited me to send a couple of short script samples.

As a playwright, I had some short plays — ten- or twelve-page one-acts — and I mailed those to Randall. On Halloween night of 1989, the phone rang in our one-room apartment, which was a four-floor walk-up on Christopher Street. Kate answered and was astonished to hear the radio come out of her phone. It was Garrison’s voice, and he asked to speak with me. She handed the phone to me, and I heard that familiar voice say hello, and explain he was launching a show and looking for a writer. He asked if I had any short pieces. I stammered that I had sent him a couple of short plays, and Garrison said he was looking for very short pieces — one or two pages. I replied that I had one of those, and he said, “Good. Come by the office tomorrow.”

I hung up, dazed. Of course I didn’t have anything of the kind, and of course I was determined to write one that night. I decided to walk through Greenwich Village and see what I could come up with. Halloween night in the Village in 1989 was both more anarchic and friendlier than the current corporate version of Halloween. I walked through the streets, noting the drag costumes, which would today be categorized as legendary, writing down bits of overheard dialogue, and then I came back to the apartment and wrote something that I hoped to be simple and honest and a little funny. It was in the form of a letter from New York, written by a young man to his girlfriend back in Missouri.

I typed it up on the best quality paper I had (yes, this was before word processing, so it was actually put through a typewriter), and the next day I reported to the American Humor Institute. It was a simple office, with a couple of rooms, one of which was occupied by Jennifer Howe, the endlessly cheerful and efficient manager of a million things GK. She greeted me and then Garrison came out, we shook hands, he was taller than I had anticipated, and we sat down in his office.

He asked the polite questions about where I had come from and I remember stammering. Even though I was 34 at the time and had worked in theaters for a dozen years, this was an opportunity like none I’d ever had. Then Garrison said, “Let’s see what you have.”

I handed him my two-page piece. He took it, and started reading. I hadn’t expected that. Silence. Extended silence. Fortunately, I had lived in Minnesota long enough to be comfortable with silence. My two pages on his desk, Garrison scowling down at them. Then he pulled out a pen and started editing. I could see him crossing lines out, writing in the margins. His lips pursed, serious, unsmiling. Finally, he looked up.

“Good. Is there a second act?”

As far as I knew, I was being interviewed for a staff writer position. I figured he was testing me — could I come up with a continuation of the story? I said, “Yes. Maybe she writes him back.”

Garrison stared in the distance for a moment, then said, “No.”

Then he pitched a wonderful idea for a second act. I wish I could remember what he said. I just remember it was great, a funny twist to the story, which opened it up. Then he handed me back my pages and said, “Can you come back in a day or two?” I said yes, correctly interpreting this as “Please rewrite this and return.”

I set a time to return with Jennifer and walked out in the hall. I looked at the pages Garrison handed back to me. During those minutes of scowling and editing, he had added hilarious jokes. It was my first experience of seeing him hard at work as a humorist — which was skillful, serious work.

I did the rewrites, typed up the new version, and returned in two days. As before, I walked in, was greeted by upbeat Jennifer, and went into Garrison’s office.

“What’chu got?”

I handed him the pages. Once again, silence as he read. He looked as serious as ever, but this time when he put the pages down, he said, “This is good. How much do you want for it?”

I was floored. I thought I was applying for some version of a staff job. I had no idea how much public radio paid — specifically how much public radio (or Garrison) paid for a two-page script.

I stammered around and finally said, “Well, I generally hope to make about $500 a week.”

A pause. I thought to myself, “Damnit, I asked for too much.”

Then he said, “I’ll give you $750.” And he had Jennifer write me a check on the spot. Somehow, he knew I needed the money. Among the many extraordinary qualities of Garrison is his visceral unbroken connection with people struggling to pay the bills. He has never forgotten what that was like.

I became a contributing writer, and it defined for me what getting your big break meant. The theater I was part of was a wonderful off-off-Broadway company, which meant our work was exciting and there was no money and we performed at the Home for Contemporary Theater and Art on Walker Street, a theater carved out of a storefront, with seating for something like 80 people, and a backstage with one tiny dressing room and a bathroom we shared with the audience. I went from the sense of performing for an audience in the palm of your hand to ARCA’s first show at BAM, on an immense stage with a Broadway orchestra populated by world-class musicians and led by Rob Fisher. It was like being shot out of a cannon and finding yourself flying in a dream.

During that time, I found myself riding back to Manhattan in a limo with Bob Elliott and his son Chris. I was introduced to Renée Fleming and Pete Seeger and Victor Borge. I traveled to the Grand Ole Opry and London and Seattle and Memphis. I was friends with Rob Fisher and Broadway musicians and Rich Dworsky and Tom Keith. (The sweetest man in the world; much missed.) Years later, I met Robert Altman and sat next to Kurt Vonnegut at the premiere of the PHC movie. It was the ride of a lifetime.

I learned many things from Garrison over the years. (I wrote for the radio show steadily for four or five years, until my TV writing took up too much time. I then shared a story credit with Garrison for the PHC movie, and I wrote again for the radio show the fall he was getting back to full steam following his stroke.)

Thing One: GK is a singular genius, a writing machine that I have never seen duplicated. I wrote five minutes of a two-hour show; Garrison wrote the rest. My usual writing consisted of short sketches, and then narrative pieces about the city we were touring to. The rest was Garrison. The idea that for 39 weeks each year, Garrison would create a two-hour show, writing 95% of the material — and somehow weaving a vision of music through it all — remains a high-wire feat unlike any in American popular culture.

Thing Two: It’s all just material. Our process was for me to turn in four or five short pieces on Thursday. There was a Friday afternoon read through of all the material for that week’s show. Garrison would show up with reams of sketches. In the first year of ARCA, there was always a 10- to 14-page continuing drama of Gloria, played by Ivy Austin, about the life of an aspiring singer in New York, as well as the other sketches that repeated every week (Duct Tape, Dusty and Lefty, Guy Noir, etc.), as well as a couple of mine. After the read through, Garrison and I would repair to his office and he would select the pieces that he thought worked, and which ones needed revision. The first week, I remember he took one of his ten-page scripts, and methodically crossed out page after page, until he finally circled one paragraph. “I’ll come back with something.” The next morning he appeared with a new eight-page script, with that one paragraph forming its core. Not many people could do this (and produce any quality, let alone sustained brilliance) — but the underlying lesson was that it’s all just material. Don’t be precious. Let it go, the good things will come back to you. Pick and choose good things and put the blocks back together in a new arrangement. It’s just material.

Thing Three: Come at a story from the side. One horrible misconception of Garrison is that he spins homespun stories from the heartland. Nothing is further from the truth. Garrison started out writing for The New Yorker, and that means a lineage from James Thurber and S. J. Perelman and E. B. White. One writing technique he guided me toward was coming at things from the side. If you want to land at point K, don’t start at point J. Start way off to the side and come to things indirectly. There’s a tremendous delight an audience feels when they suddenly see how things have tied together in a completely unexpected but understandable way. He employs this technique in the monologues most famously. (Note: He always writes the News From Lake Wobegon in a mysterious cone of silence. He’d simply show up on Saturdays and deliver them — never went over them in rehearsal. If I had to guess, he’d write it out Saturday morning, and because he has what seems to be a photographic memory, he’d be able to deliver it that afternoon.)

Thing Four: It’s a live show; keep it live. From doing hours of live early morning radio he realized that part of the excitement of a live show is to not overprepare. Or, rather, to bake the cake right in front of the audience. The audience delighted in seeing the flow of the show — in seeing Garrison do the high-wire act of creating a two-hour entertainment that held together, but was created right before their eyes. This was both true and not true. The musical acts were obviously booked long before the show; the scripts were rehearsed —well, read through on Friday, and then read through again on Saturday — but the feeling was that we were putting the whole thing together right in front of the audience’s eyes. Garrison always pushed the deadlines for preparing for the show to the final moments — I remember one week in New York when, at about half hour before air, he nonchalantly said he was going back home to get a belt (not such an easy trip in the city, to go from midtown to the Upper West Side and back!) — and he actually ducked out. There was tightly controlled panic, and prayers that he’d come back in time, and sure enough, with only moments to spare, he walked in, now fully dressed with a belt, and walked out on stage and did his pre-show. I think that was all part of a conscious and subconscious effort to keep the show in the moment: This is happening right now, we’re all in this together, let’s hope it turns out for the best.

RICHARD DWORSKY, MUSIC DIRECTOR AND KEYBOARD PLAYER

After a more than 40 year association with Garrison Keillor and his radio show A Prairie Home Companion, people often ask me how that relationship began. The answer is short and simple. My parents…Bob and Shirley. Dad had owned the World Theater and the attached Schubert Apartments since 1970. A Prairie Home Companion was looking for a permanent home and, in 1978, found it at the World Theater (later renamed the Fitzgerald Theater). Sadly, Dad passed away that same year, and Mom became the owner/landlord. She knew nothing about business (that was handled by others), but she did become friends with the show’s producer, Margaret Moos. Mom had been impressed by a talented Russian and Yiddish singer, Sima Shumilovsky, who had recently arrived in St. Paul from the Soviet Union. Mom thought that Sima would make wonderful guest on A Prairie Home Companion and dragged Margaret to a little a cappella performance Sima gave in a basement room at the St. Paul Jewish Community Center. Margaret was very impressed but a little cautious, saying, “Sima is great, but she needs an accompanist”. Mom immediately replied “My son, Richard, can play piano in any style and can learn a song immediately by ear” etc. Margaret was sold on the idea. Mom then came to me with the plan for my approval. Not considering myself a Russian/Yiddish folkie, my response was less than enthusiastic.

But Mom was persistent and begged me, saying “Come on. It’ll be a mitzvah” (Hebrew for a good deed). Sima and I performed on the radio show in February of 1980, and it went so well that we were invited back several more times. After a few shows, I was given an opportunity to do a solo tune. Garrison took notice and invited me back as a solo performer and to accompany him and various other guests. This all led to me eventually becoming A Prairie Home Companion’s pianist/music director for decades.

The moral of the story? Listen to your mother! Every once in a while, she just might be right…and in a way that can change your life.

A short story about my dad, Bob Dworsky and the World Theater

After his service, Bob graduated from the University of Minnesota Law School in 1949 and began his law practice in St. Paul. He was admired and respected as a brilliant attorney, and in 1962 formed the “Dworsky & Rosen” law firm in partnership with attorney William S. Rosen. Beginning in 1956, he performed legal services for his old college friend, Billy Weitzman. Bob eventually became a development partner in Billy’s company, William H. Weitzman and Associates, a firm which designed and built apartments in the Twin Cities (Minneapolis and St. Paul).

Upon Weitzman’s death, Bob retained his ownership share in many of the buildings, and formed his own company, Multifam Corporation, to manage them. But he was granted sole ownership of the Shubert Building apartments and the adjacent World Theater (later renamed The Fitzgerald) in St. Paul, which became the permanent home of Garrison Keillor’s A Prairie Home Companion on Minnesota Public Radio. In 1978, MPR had approached Bob about renting the theater during broadcast weekends. Bob was a lover of the arts and generously gave MPR use of the theater for a flat fee of $90 per week. The show’s producer at the time recalled that “this fee was supposed to cover heating and lighting. I can’t imagine it came close.”

Bob passed away that same year, but Shirley never raised the rent. MPR eventually purchased the theater from Shirley.

CHRISTINE TSCHIDA, PRODUCER

I have lots of memories about the show in the early days of its reincarnation as The American Radio Company of the Air, then, The American Radio Company, and eventually A Prairie Home Companion once again.

Though I am from Minnesota/Mac grad/and had attended a couple of broadcasts of the original APHC in the Twin Cities, I was actually working at The Brooklyn Academy of Music in New York when Garrison returned from Denmark and started ARCA. My college friend Ken LaZebnik was living in New York at the time, and I’d occasionally get him comps for BAM shows. So, when he told me he was doing some writing for Garrison’s new radio show — which was actually renting one of the theaters at BAM in that first season, I asked him for tickets to that in return. A couple of months after seeing it, Ken told me that the show needed to find a new producer, and that’s how I came to be hired by Minnesota Public Radio while living in New York. I had produced plenty of theater and dance tours, but I had never really worked in radio, so it was good that there were smart people who knew the technical/broadcast side of the business, because I certainly did not.

The show was a bit of a nomad those first couple of seasons. BAM wasn’t really the right place for it, or for Garrison’s audience, which would happily find its way to midtown Manhattan from Connecticut and New Jersey and beyond. Somewhere with less expensive rent and production costs was better, and not in a sketchy (at that time) neighborhood in an “outer borough” would be better. So the “second season” (the first one that I worked on) found us renting The Lamb’s Theatre on 44th Street in Manhattan. At 350 seats, it was a much better fit for a show that was just getting started at building an audience than the cavernous BAM Opera House was.

Garrison had connected with Rob Fisher to put together a wonderful 16-piece band they called The Coffee Club Orchestra (with a smaller group called the Demitasse orch). There was also a terrific musical arranger, Russell Warner, who would compose theme music for the sketches and commercials. I recall “The Water March” for a campaign to promote drinking eight glasses of water a day (which didn’t last) and others, like Café Boeuf, Rhubarb, and Coffee that did. There was a running soap opera about a young woman in New York called “The Story of Gloria” and Ivy Austin and Richard Muenz were regulars (more or less) augmented by Tom Keith (who didn’t want to travel) and other terrific New York based actors like Alice Playten and Lynne Thigpen.

So, the first show I ever worked on was at The Lamb’s Theatre, and I don’t remember all of the details exactly. I think the guest list may have included The Gregg Smith singers (they made a few appearances on shows in that period) and perhaps Victor Borge was on? I do distinctly remember leading him up a circular staircase offstage right to a dressing room area that we had designated for him, brushing cobwebs out of the way as we went. He was a very good sport about it.

Prior to that show, I got my first stopwatch. We had a meeting or two earlier in the week in the show’s offices in the big Republic Bank Building on the corner of 14th Street and 8th Avenue. (Surely this must have been the inspiration for Guy Noir’s Acme Building, right?)

We read through first drafts of a couple of scripts, talked about possible music selections from the orchestra and the guests, and called the final tech/dress rehearsal for noon on Saturday at The Lamb’s.

Saturday we ran through musical numbers, which I timed, waited for Garrison to arrive with revised, and new and different scripts, and went through all of that material. Sometime mid afternoon, I sidled over to my friend Ken, with my list of timings in hand, and said, “So, we have all of this … stuff now. Who figures out how it all comes together to be a show?” I could see a look of fear on Ken’s face. The fear that he had recommended a complete idiot to be the producer. Still, he smiled, chuckled, and said, “Well, YOU do.” And so, the learning curve began.

The first “tour show” I worked on was shortly thereafter — a broadcast from the Mark Twain home in Hartford, CT, but the show traveled to many exciting places — London’s West End, Edinburgh, Dublin, Berlin, and the Reading Room of the New York Public Library.

My favorite tour story, though, was the Birmingham, Alabama, Blizzard story, where the city shut down, and the company was stranded for an entire extra day because nothing was moving. Of course, the show went on — despite being told repeatedly on Friday afternoon and evening that we should cancel it. Tom Keith would tell everyone that I “made him” rent a car when his connecting flight from Atlanta was canceled (I did), but admitted later on that it was great that we had it available so he could run a reconnaissance mission out to the Birmingham airport. By now, everyone has likely heard the stories about how 500 people managed to get themselves to the theater for the broadcast (the guy with the keys to open it up for us used skis); how Emmylou Harris’s tour bus was 50 miles outside of town an hour before broadcast time; how our truck driver Russ Ringsak had to go pick up the last member of the Dixie Hummingbirds AND his pregnant wife from the other side of town in the cab of the semi, and they made it onstage for the closing number of the show. It was nerve-racking as we went through it, but so much fun to think about now.

Recognizing that this is a 50-year anniversary, I want to mention some things that I think about, occasionally, related to the show and the world that it was/is a part of.

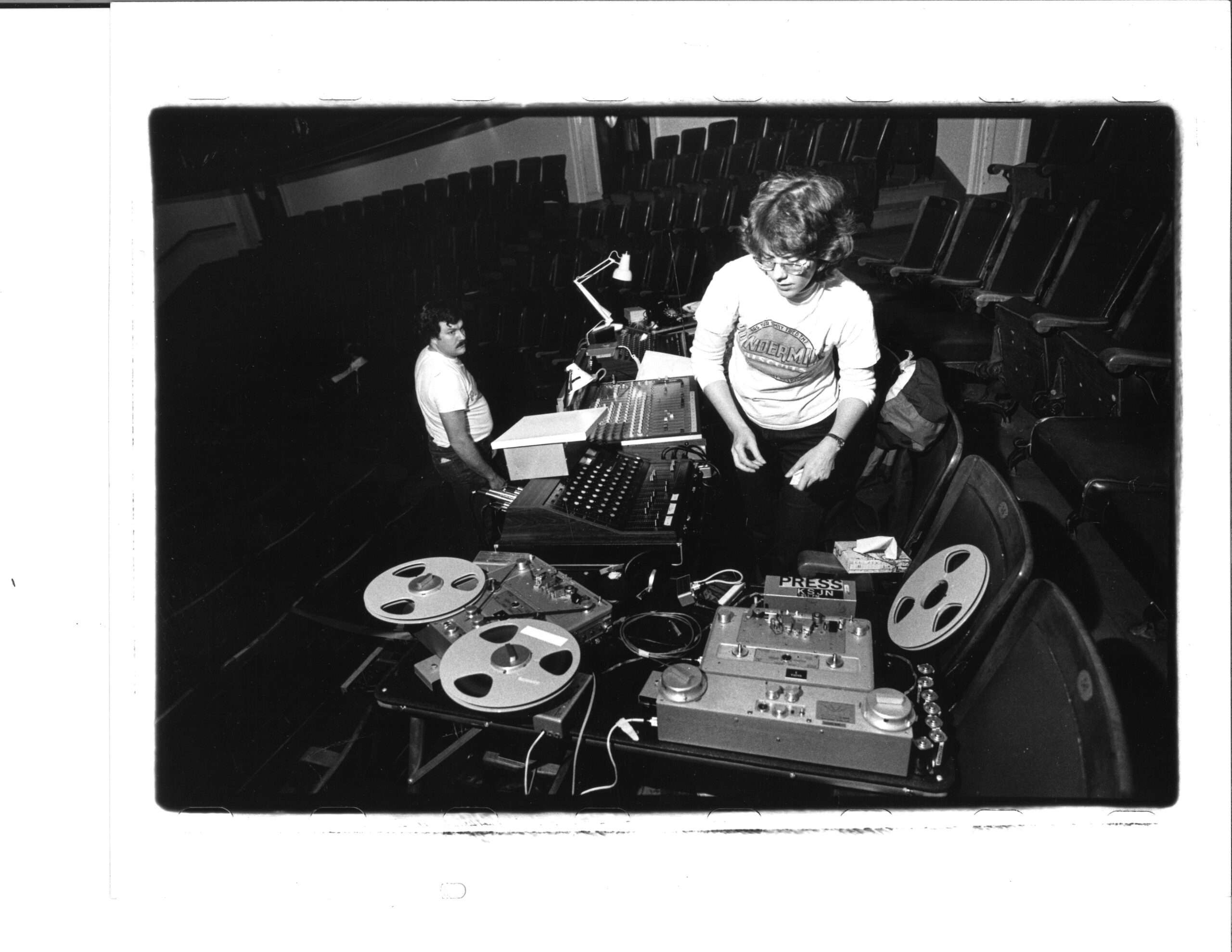

One thing is TECHNOLOGY. We used to have scripts come in paper form that we would feed into a xerox copier that we carried with us to every theater we performed in (or rented on-site.) Revisions were done by hand sometimes, sometimes even mid broadcast, as the script was being performed. Research wasn’t done via the internet or Wikipedia. We used books, the library, and Russ Ringsak’s on-site observations from the road.

The first “mobile phones” that we had were enormous. I remember that technical director Scott Rivard had one that was roughly the size of a shoebox. We had to have phone cables installed in each theater in order to be able to transmit the show for uplink for broadcast. There was one night in New York (the show by then hand moved from The Lamb’s Theatre to Symphony Space and then to The Town Hall) when something went wrong with that uplink connection, and we had to dash from Town Hall to WNYC studios down by City Hall in lower Manhattan carrying two reels of tape so that the show could get on the air for those who tape-delayed it on Saturday, and for the Sunday rebroadcast.